Last week we announced that we are now ranking search results on https://sourcegraph.com in order to prioritize relevant as well as reusable code. We consider this Sourcegraph’s code intelligence platform’s first major victory of many, and a booming herald for a new era of code search.

The effort to bring ranked results to our public instance was a concerted effort of four developers across two teams (Search and Code Intelligence), but it took only a week of wall-clock time to design, implement, and deploy. The speed at which we were able to deliver this feature speaks volumes about our core data architecture.

For the past three years at Sourcegraph, I have been amassing a giant compiler-accurate index of source code. And like a giant dork, that giant pile of data has just been sitting there enabling only the most basic of code navigation operations: go to definition and find references. The ranking effort is our first official foray into consuming this data in a more interesting way.

And we’ve acquired a taste for it.

Ranking is a only small amuse-bouche of what we have planned in the future.

High-level overview

PageRank is an algorithm created by Google co-founder Larry Page in 1998 to assign a numeric value to each webpage indexed by the search engine. The algorithm takes as input a graph representing the set of webpages and links between them, and outputs a probability of a user landing on a particular webpage (for every webpage) by randomly clicking on links. Webpages with many or highly relevant backlinks will have a higher PageRank score and are presented higher in the list of matching search results.

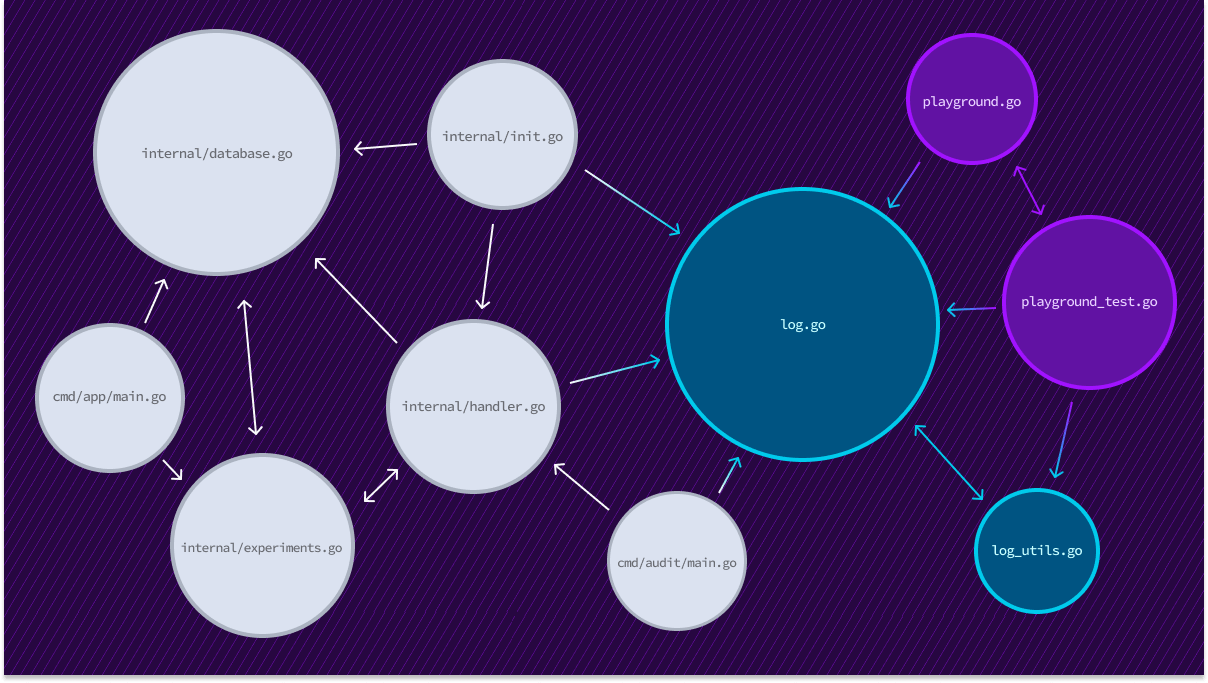

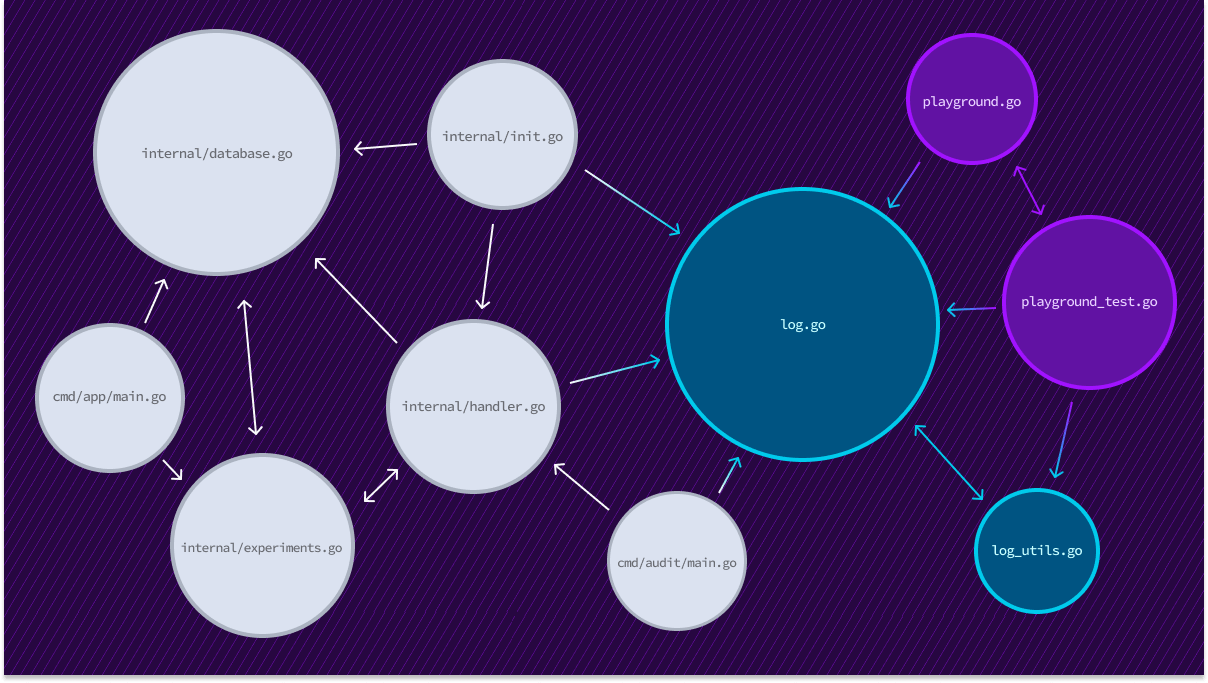

We utilize the PageRank algorithm to rank source code results in a similar way. In our current implementation, we construct a graph of source code text documents where an edge between two documents indicates a reference of a symbol (variable, function, type, etc) defined in another file.

PageRank values calculated over this graph “flow” to the text documents that have the highest concentration of code use or re-use. This tends to surface results that have high relevancy to a search query by bringing popular definitions and representative usages to the top.

Larry Page himself states that “the computation of PageRank is fairly straightforward if we ignore the issues of scale”, and the Wikipedia article for the algorithm is filled with descriptions of eigenvector centrality of a stochastic matrix via Von Mises iteration. To get ranking results as quickly as possible so we can validate and iterate on the properties of the graph structure itself, we made the pragmatic choice to use Apache Spark, as it provides several implementations of PageRank out-of-the-box (please see xkcd #353).

Treating PageRank as an opaque box, there’s still the interesting bit of constructing the document reference graph and consuming the resulting text document ranks. The next section explains major chunks of work that went into the creation of this data pipeline.

Timeline

We begin our work on ranking hearing only loosely-described north stars and a vague expectation of experimental outcomes. Technical discussions between teams begin and ownership boundaries are loosely drawn.

We constructed an initial ranking service between October 3rd and 6th, which had only stub implementations for background indexing jobs and user-specified queries for ranks. This pull request was originally created as an initial way to discover the proper API boundary between the Search and Code Intelligence teams, as evidenced from the discussion.

Between October 10th and 12th, I took a small journey to experimentally calculate PageRank over small reference graphs. This was mostly a familiarization exercise for myself, and the code that lands in this PR has not been active on any machine (outside of the four developers actively working on this effort, but even that seems too high), despite still being usable on the main branch. Stay tuned for future updates on the evolution of this code!

At this point, the ask for PageRank deliverable becomes concrete, and we settle on an adequate, although incredibly brisk, timeline. On October 23rd, our effort begins in earnest.

We begin by concentrating on the construction of a graph over which we can run PageRank. Our chosen solution employs a background worker that periodically exports code intelligence data into CSV files in a GCS bucket. For each repository for which we have precise code intelligence data, we export several files containing data related to the tip of that repository’s default branch.

First, we output documents.csv, which correlates a repo and file path pair with a randomly generated identifier (increasing integers for the sake of simplicity in this example). These items correspond to the white vertices in the graph of text documents shown earlier in this post.

pathID,repo,path

1,github.com/sourcegraph/blog-post-example,cmd/app/main.go

2,github.com/sourcegraph/blog-post-example,cmd/audit/main.go

3,github.com/sourcegraph/blog-post-example,internal/database.go

4,github.com/sourcegraph/blog-post-example,internal/experiments.go

5,github.com/sourcegraph/blog-post-example,internal/handler.go

6,github.com/sourcegraph/blog-post-example,internal/init.go

Next, we output references.csv, which corresponds to the edges between the white vertices. Such an edge is output when there is a direct reference from a variable defined in another file.

from,to

1,3

1,4

2,5

3,4

4,3

4,5

5,3

5,4

6,3

6,5

To support references between repositories, we output monikers.csv, which will declare a set of monikers that are either declared in or referenced by a particular path. If one repository declares an import moniker, and another repository declares an export moniker with the same scheme and identifier, then we create an edge between the documents across repositories.

pathID,monikerType,schema,identifier

1,import,gomod,github.com/sourcegraph/log/Logger

1,import,gomod,github.com/sourcegraph/log/Logger.Log

5,import,gomod,github.com/sourcegraph/log/Logger

5,import,gomod,github.com/sourcegraph/log/Logger.Log

6,import,gomod,github.com/sourcegraph/log/Logger

6,import,gomod,github.com/sourcegraph/log/Logger.Log

We would later round out this implementation by also pruning irrelevant data from the target GCS bucket as newer indexes for repositories replace older indexes. Since the landing of this export task, it has become the basis of several other solutions currently in-flight (details to come in future blog posts).

By October 27th, we had a few successful runs of a distributed Spark job over the graph described by these CSV files and hand-vetted the document scores results to ensure our mental model and reality match. In order to build a better intuition of how PageRank will relate to source code documents, we constructed several variations of the graph:

- Edges are directional, and

a -> bexists whenarefers to a symbol defined inb - Edges are directional, and

b -> aexists whenarefers to a symbol defined inb - Edges are undirected, and both

a -> bandb -> aexist when one document refers to a symbol defined in the other

Interestingly, we ended up running PageRank over an undirected graph, as directional edges tended to rank auto-generated files with tons of definitions (e.g., a protobuf code gen) very highly, but rank main-like files that refers to lots of definitions but defines few themselves very low. This is the opposite of what we want: the glue code with few inbound edges but lots of (unique) outbound edges indicates the collision of two program boundaries. These usages are precisely the ones that should be advertised, and using undirected edges gives us the best of both directional options by boosting files with multiple distinct edges (whether they are inbound or outbound).

We could then begin to consume PageRank outputs into our database, for use in the stub service implementation referenced earlier. This “completes the loop” of data from the Sourcegraph instance’s point of view: we are continuously refreshing our output graph, and continuously re-consuming PageRanks cores as we re-run the computation.

The output data that Spark gives us is also a series of CSV files in a second GCS bucket, each with the following form:

repo,path,rank

github.com/sourcegraph/blog-post-example,internal/handler.go,9.657402401

github.com/sourcegraph/log,logger.go,15.567945095

github.com/sourcegraph/blog-post-example,internal/database.go,10.999427919

github.com/sourcegraph/blog-post-example,internal/experiments.go,8.604131051

github.com/sourcegraph/blog-post-example,internal/init.go,7.266468968

github.com/sourcegraph/blog-post-example,cmd/app/main.go,0.703945210

...

Each CSV file (of which there are hundreds of thousands) is an equal-sized shard of results. The ranking scores for a single repository may be spread out over multiple files, thus we have to do some clever aggregation on our end to aggregate all of a repo’s score. Thankfully, we have a bit of expertise and a bag of tricks that help us ensure we can consume and aggregate this data without significantly increasing resource requirements on our primary database.

On October 30th, we updated the conditions that tell our indexing server when a repository has had a relevant update. Before, this method would only return repositories that we know have received a Git push to remote since the last indexing attempt for that repository. After, this method will also return repositories for which we have updated ranking scores. This allows us to pack the search indexes such that documents in a repository are ordered by their ranking.

Although we’ve covered the bulk of the data pipeline, other improvements have occurred, and we continue to iterate on ranking heuristics at every level of the stack (graph construction, PageRank algorithm variants, index-time rank packing of index shards, query-time resorting of search results, etc. ).

Looking to the future

In a little bit over a week, we built a data pipeline to bring incredible new value to Sourcegraph that will fundamentally improve the user experience for code search and code navigation. As our Head of Engineering notes, we will continue to make improvements to our search relevance in every dimension over the coming days, weeks, months, and years. One improvement I’m particularly excited to jump into is running PageRank over much larger data with higher granularity: individual symbols instead of documents.

We have a pile of precise data, and now we have a proven way to compute different properties over our global source graph at scale.