In Part 1 of this optimization story, we detailed how Sourcegraph can resolve code intelligence queries using data from older commits when data on the requested commit is not yet available. The implementation lies completely within PostgreSQL, and the queries run with very low latency (< 1ms). We boldly claimed that our fears of scalability were no longer cause for concern.

Turns out that claim was a half-truth (if not a lie) as Sourcegraph solves the problem well, but only at a particular scale. There is an entire class of enterprise customers who could benefit from this feature as well, but the speed at which the code moves is a huge obstacle to overcome when calculating visible uploads on demand.

Because our implementation relies on a graph traversal within PostgreSQL triggered frequently by user action, we need to limit the distance each query can travel in the commit graph. This is to guarantee that single requests are not taking a disproportionate amount of application or database memory and causing issues for other users. The introduction of this limit brings stability to the Sourcegraph instance by capping the maximum load a single query can put on the database. But there is a downside: there are many shapes of commit graphs that will fail to find a visible upload traversing a limited commit graph, even if the distance is not too large.

In Part 1, we stopped tracking the distance between commits as a performance optimization. Because of this, we no longer have a way to limit by commit distance. Instead, we enforce a limit on the number of total commits seen during the traversal. This means that one query will travel a smaller distance on a commit graph with a large number of merge commits, and a larger distance on a commit graph that is mostly linear.

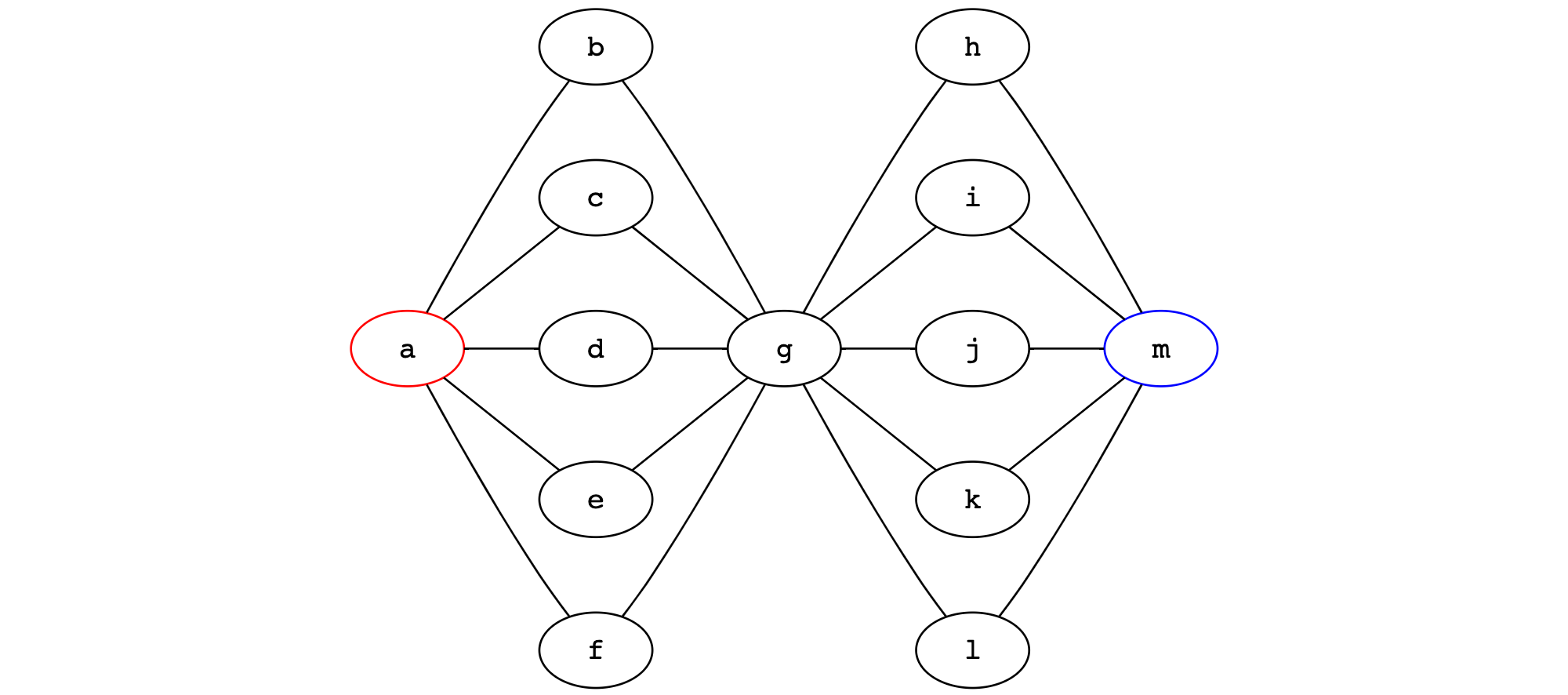

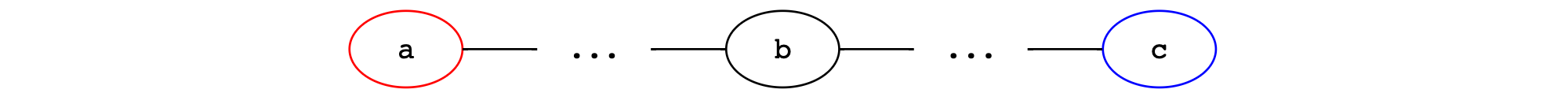

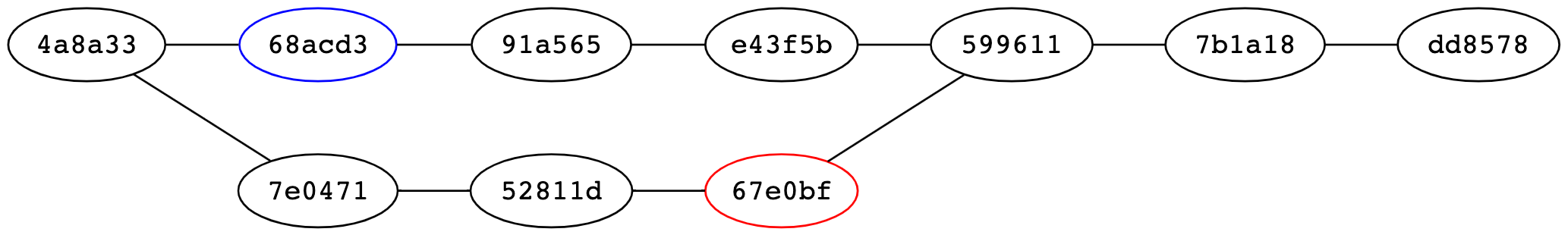

The following Git commit graph illustrates this difference. Searching from commit g, we could find index data on commits a and m, both only two steps away. However, if we had a limit of 10, we would see only the commits directly adjacent to g and would hit our limit before expanding outwards.

Another issue is high commit velocity. Suppose that we have a hard limit of viewing 50 commits. We will then be able to look (approximately) 25 commits in a single direction. If the process for uploading LSIF data only happens every 50 commits, on average, then there will be pockets of commits that cannot see far enough to spot a relative commit with an upload. This turns out to be common in the case of large development teams working on a single repository.

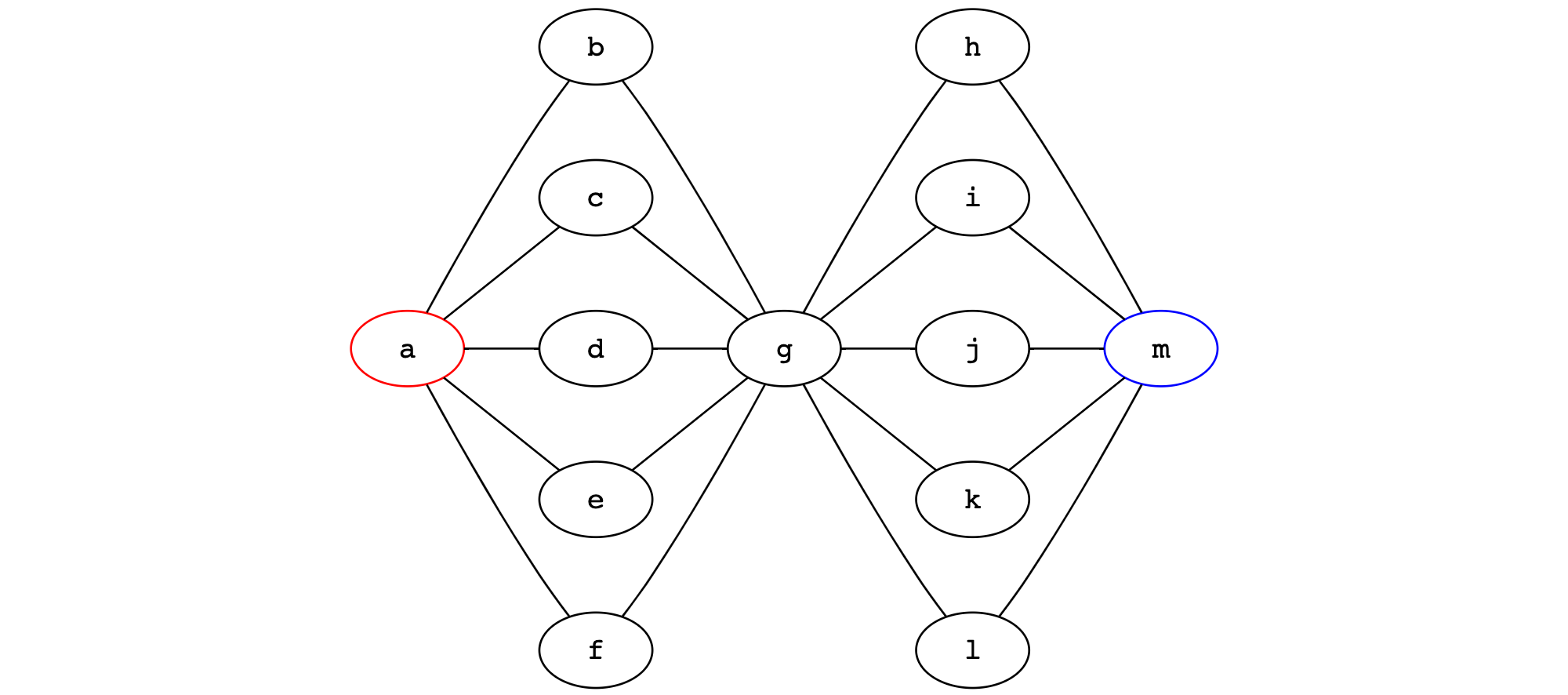

The following Git commit graph illustrates this, where commit b could simply be stranded on both sides by ancestor and descendant commits with code intelligence data just out of reach.

A better design

In these circumstances, bounded traversals are a fundamental design flaw. To get rid of this constraint, we turn to a technique that was very successful in the past: index the result of the queries out of band. This technique forms the basis of our search: we create a series of n-gram indexes over source text so we can quickly look inside text documents. This technique also forms the basis of our code intelligence: we create indexes that contain the answers to all the relevant language server queries that could be made about code at a particular revision.

In the same spirit, we eschew graph traversal at query time and calculate the set of visible uploads for each commit ahead of time (whenever the commit graph or set of uploads for a repository changes). This reduces the complexity of the query in the request path into a simple single-record lookup.

This change was made in our 3.20 release (over pull requests #12402, #12404, #12406, #12408, #12411, and #12422) and introduced 2 new tables: lsif_nearest_uploads and lsif_dirty_repositories.

The lsif_nearest_uploads table stores what you would expect. For each commit that has a visible upload, there is a row in the table indicating the source commit, the identifier of the visible upload, and the distance between the source commit and the commit on which the upload is defined. Multiple uploads may be visible from a single commit as we look in both ancestor and descendant directions. There may also be multiple visible uploads in the case of different languages or different directories at index time, but we’ll hand-wave around these particular details for now.

| repository | commit | upload_id | distance |

|---|---|---|---|

| github.com/sourcegraph/sample | 323e23 | 1 | 1 |

| github.com/sourcegraph/sample | d67b8d | 1 | 0 |

| github.com/sourcegraph/sample | 4c8d9d | 1 | 1 |

| github.com/sourcegraph/sample | 4c8d9d | 2 | 1 |

| github.com/sourcegraph/sample | f4fb06 | 2 | 0 |

| github.com/sourcegraph/sample | a36064 | 2 | 1 |

| github.com/sourcegraph/sample | 313082 | 1 | 2 |

| github.com/sourcegraph/sample | 6a06fc | 1 | 3 |

The lsif_dirty_repositories table tracks which repositories need their commit graphs updated. When we receive an upload for a repository, or get a request for a commit that we don’t currently track, we bump the dirty_token value attached to that repository. When we are about to refresh the graph, we note the dirty token, calculate the set of visible uploads for each commit, write it to the database, and set the update_token to the value of the dirty token we noted earlier. This ensures that we avoid a particular class of race conditions that occur when we receive an upload at the same time we’re re-calculating the commit graph from a previous upload.

| repository | dirty_token | update_token |

|---|---|---|

| github.com/sourcegraph/sample | 42 | 42 |

Example

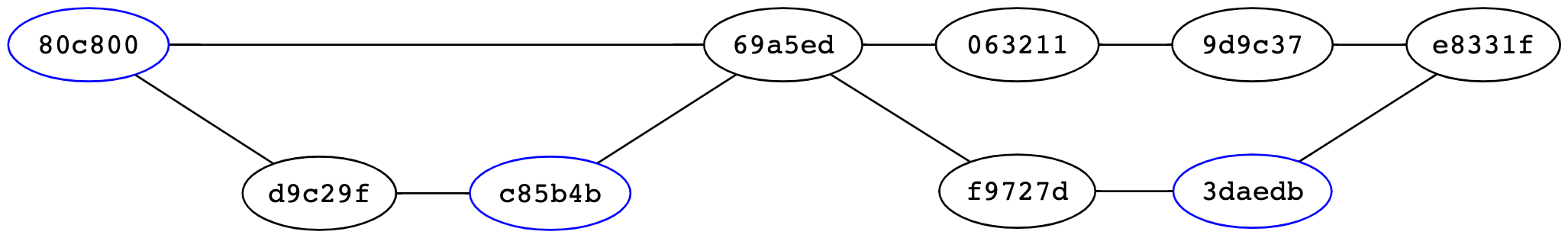

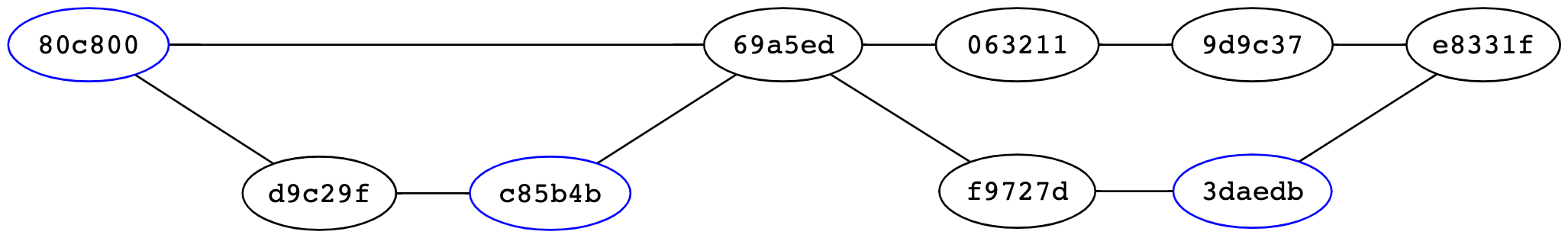

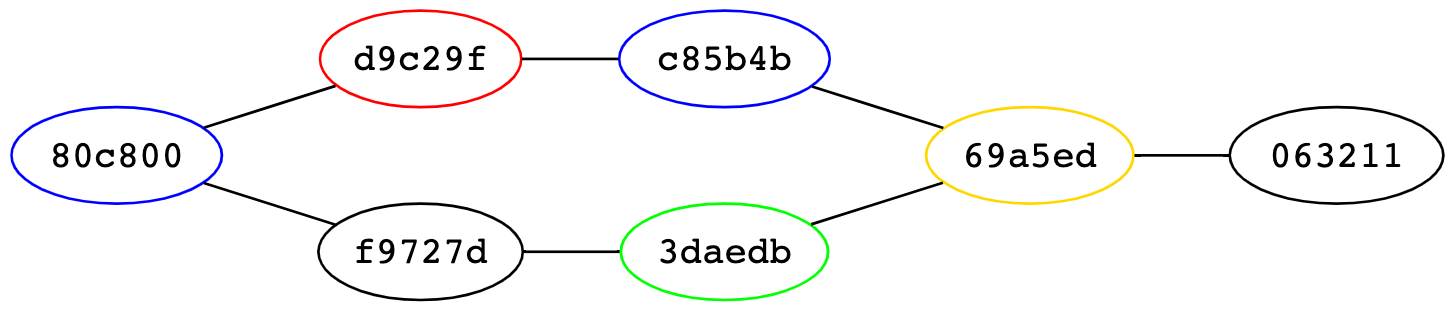

For this example, we’ll use the following commit graph, where commits 80c800, c85b4b, and 3daedb define uploads #1, #2, and #3, respectively.

The first step of the algorithm is to topologically sort each commit so that a commit is processed only after all of its parents are processed. Then we perform a simple greedy process to determine which uploads are visible at each stage of the commit. If a commit defines an upload, it is visible to that commit. Otherwise, the set of visible uploads for the commit is the same as the uploads visible from each parent (just at a higher distance).

Because each parent can see a different set of uploads, we need to specify what happens when these sets merge. Take commit e8331f as an example. This commit can see both upload #3 via commit 3daedb), as well as upload #1 via commit 9d9c37. This yields a visible set {(id=1, dist=4), (id=3 dist=1)}. As part of the merge operation, we throw out the uploads that are farther away in favor of the ones that are closer. Similarly, we may see different uploads that tie in distance (as is the case with commit 69a5ed, which can see both uploads #1 and #2 at the same distance). In these cases, we break ties deterministically by favoring the upload with the smallest identifier.

We want to search the graph in both directions, so we perform the operation again but visit the commits in the reverse order. The set of forward-visible uploads and backwards-visible uploads can then be merged using the same rules as stated above. The complete set of visible uploads for each commit for this example commit graph are shown below.

| Commit | Descendant visibility | Ancestor visibility | Combined visibility | Nearest upload |

|---|---|---|---|---|

80c800 | {(id=1, dist=0)} | {(id=1, dist=0)} | {(id=1, dist=0)} | #1 |

d9c29f | {(id=2, dist=1)} | {(id=1, dist=1)} | {(id=1, dist=1)} | #1 |

c85b4b | {(id=2, dist=0)} | {(id=2, dist=0)} | {(id=2, dist=0)} | #2 |

69a5ed | {(id=3, dist=2)} | {(id=1, dist=1)} | {(id=1, dist=1)} | #1 |

063211 | {} | {(id=1, dist=2)} | {(id=1, dist=2)} | #1 |

9d9c37 | {} | {(id=1, dist=3)} | {(id=1, dist=3)} | #1 |

f9727d | {(id=3, dist=1)} | {(id=1, dist=2)} | {(id=3, dist=1)} | #3 |

3daedb | {(id=3, dist=0)} | {(id=3, dist=0)} | {(id=3, dist=0)} | #3 |

e8331f | {} | {(id=3, dist=1)} | {(id=3, dist=1)} | #3 |

The topological ordering of the commit graph and each traversal takes time linear to the size of the commit graph, making this entire procedure a linear time operation.

The neglected scaling dimension

Well, it’s not quite linear time if you take into account some of the stuff we claimed we could hand-wave away earlier: index files for different root directories.

Many large repositories are built up of smaller, self-contained projects. Or, at least independently analyzable units of code. This enables a fairly coarse caching scheme: each time the repository is indexed (on git push, or periodically), only the units of code that have had explicitly changed since the last indexed commit need to be re-indexed.

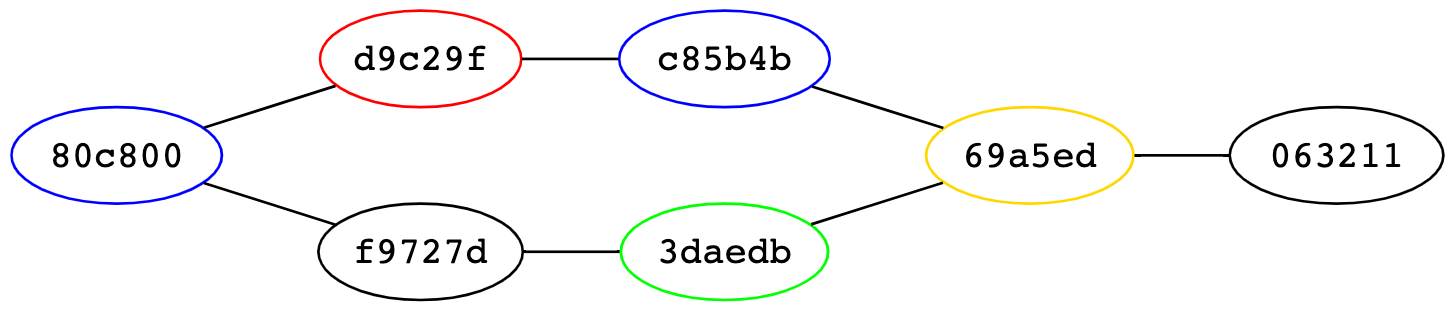

This means that there is no single nearest upload per commit: there is a nearest upload per distinct indexing root directory. To show the difference in output, we’ll use the following commit graph, where:

- Commit

80c800defines upload #1 rooted at the directory/foo - Commit

d9c29fdefines upload #2 rooted at the directory/bar - Commit

c85b4bdefines upload #3 rooted at the directory/foo - Commit

3daedbdefines upload #4 rooted at the directory/baz - Commit

69a5eddefines upload #5 rooted at the directory/bonk

| Commit | Descendant visibility | Ancestor visibility | Combined visibility |

|---|---|---|---|

80c800 | (id=1, root=foo/, dist=0) | (id=1, root=foo/, dist=0)(id=2, root=bar/, dist=1)(id=4, root=bnk/, dist=2)(id=5, root=baz/, dist=3) | (id=1, root=foo/, dist=0)(id=2, root=bar/, dist=1)(id=4, root=bnk/, dist=2)(id=5, root=baz/, dist=3) |

d9c29f | (id=1, root=foo/, dist=1)(id=2, root=bar/, dist=0) | (id=2, root=bar/, dist=0)(id=3, root=foo/, dist=1)(id=5, root=baz/, dist=2) | (id=1, root=foo/, dist=1)(id=2, root=bar/, dist=0)(id=5, root=baz/, dist=2) |

c85b4b | (id=2, root=bar/, dist=1)(id=3, root=foo/, dist=0) | (id=3, root=foo/, dist=0)(id=5, root=baz/, dist=1) | (id=2, root=bar/, dist=1)(id=3, root=foo/, dist=0)(id=5, root=baz/, dist=1) |

69a5ed | (id=2, root=bar/, dist=2)(id=3, root=foo/, dist=1)(id=4, root=bnk/, dist=1)(id=5, root=baz/, dist=0) | (id=5, root=baz/, dist=0) | (id=2, root=bar/, dist=2)(id=3, root=foo/, dist=1)(id=4, root=bnk/, dist=1) |

f9727d | (id=1, root=foo/, dist=1) | (id=4, root=bnk/, dist=1)(id=5, root=baz/, dist=2) | (id=1, root=foo/, dist=1)(id=4, root=bnk/, dist=1)(id=5, root=baz/, dist=2) |

3daedb | (id=1, root=foo/, dist=2)(id=4, root=bnk/, dist=0) | (id=4, root=bnk/, dist=0)(id=5, root=baz/, dist=1) | (id=1, root=foo/, dist=2)(id=4, root=bnk/, dist=0)(id=5, root=baz/, dist=1) |

063211 | (id=2, root=bar/, dist=3)(id=3, root=foo/, dist=2)(id=4, root=bnk/, dist=2)(id=5, root=baz/, dist=1) | (id=2, root=bar/, dist=3)(id=3, root=foo/, dist=2)(id=4, root=bnk/, dist=2)(id=5, root=baz/, dist=1) |

The size of the table here (relative to the simple table produced by a single-root repository) is the thing to note. Let’s say a repository has n commits and m distinctly indexable directories. Each commit then can see up to m uploads, which drastically balloons the cost of merging 2 sets of visible uploads. This further impacts performance in the presence of many merge commits.

We drastically underestimated the value of m for some enterprise customers.

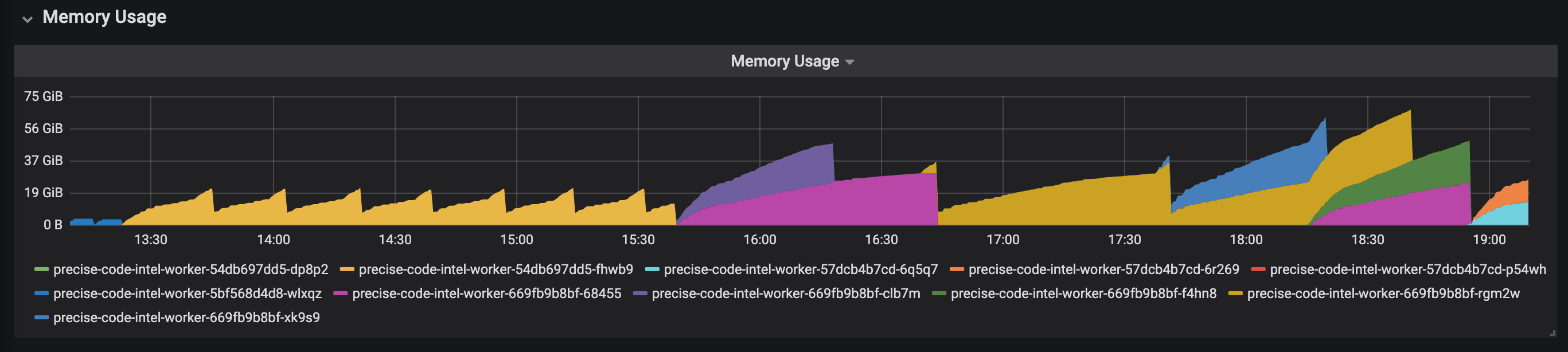

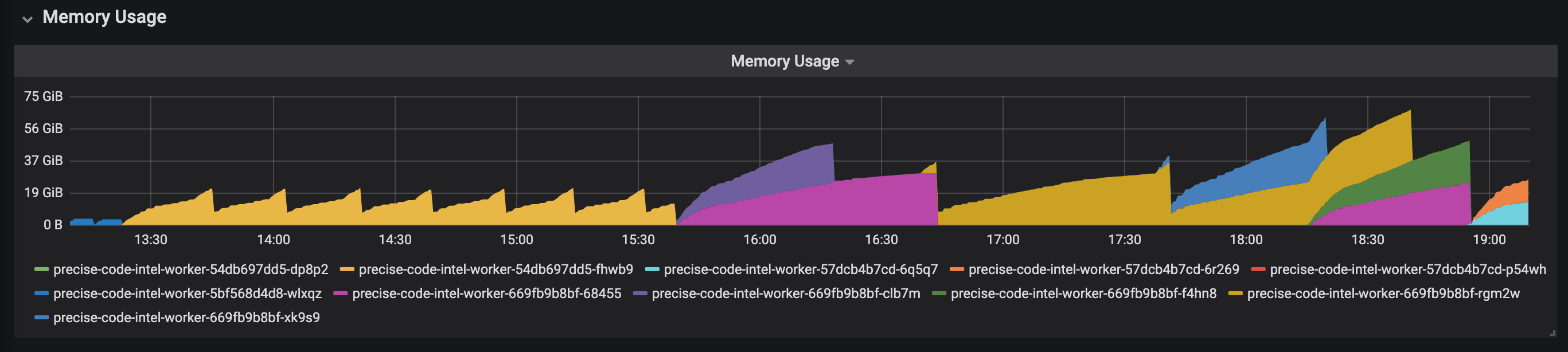

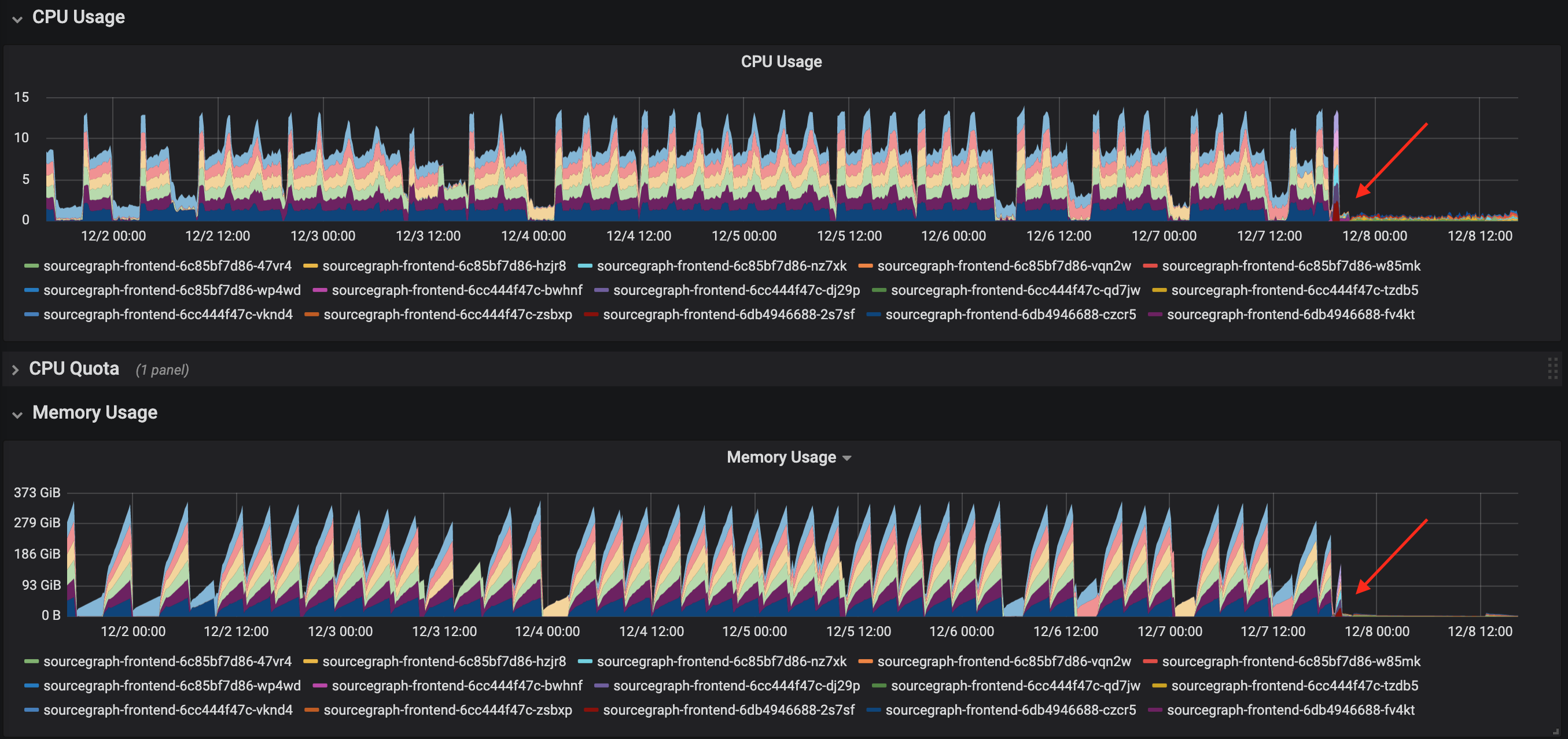

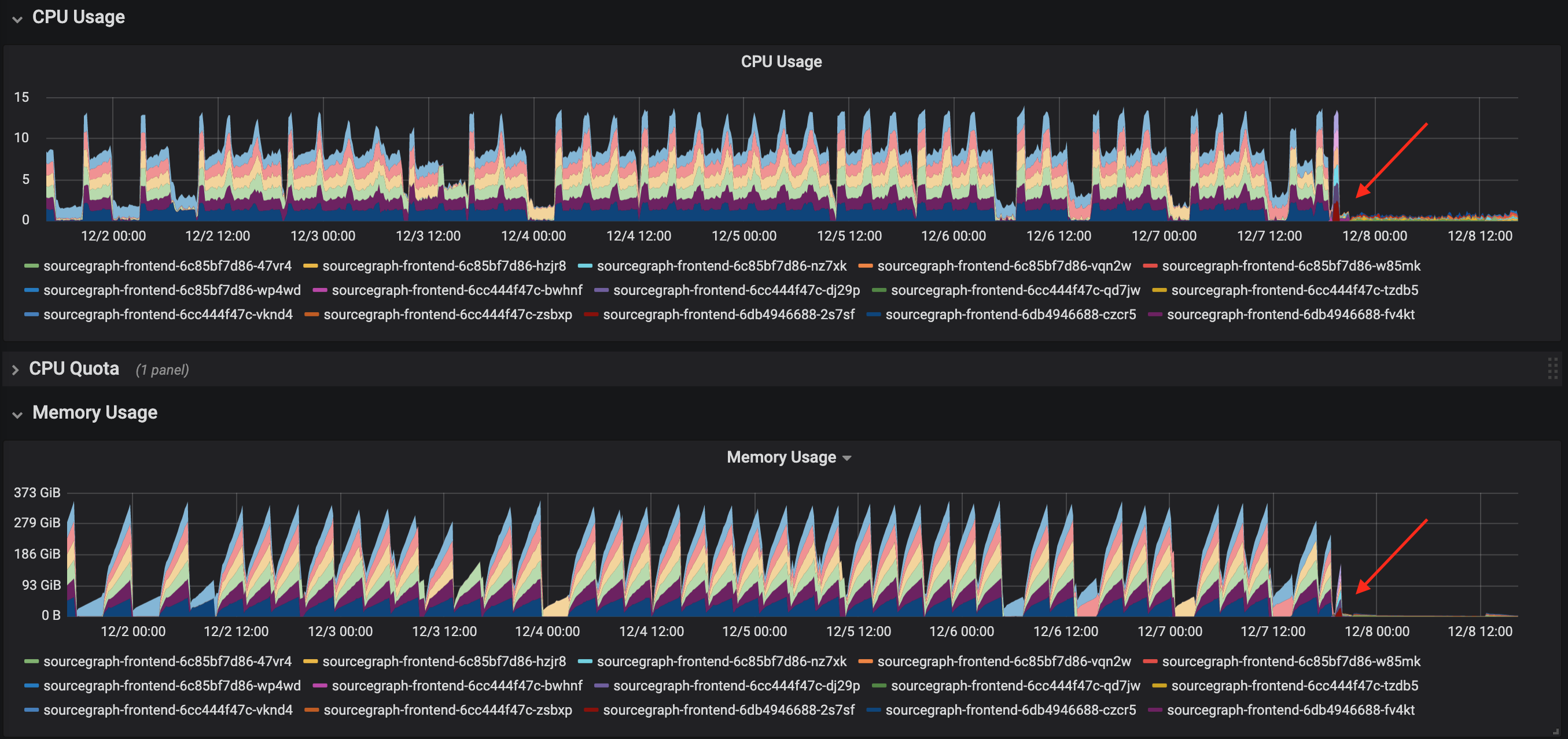

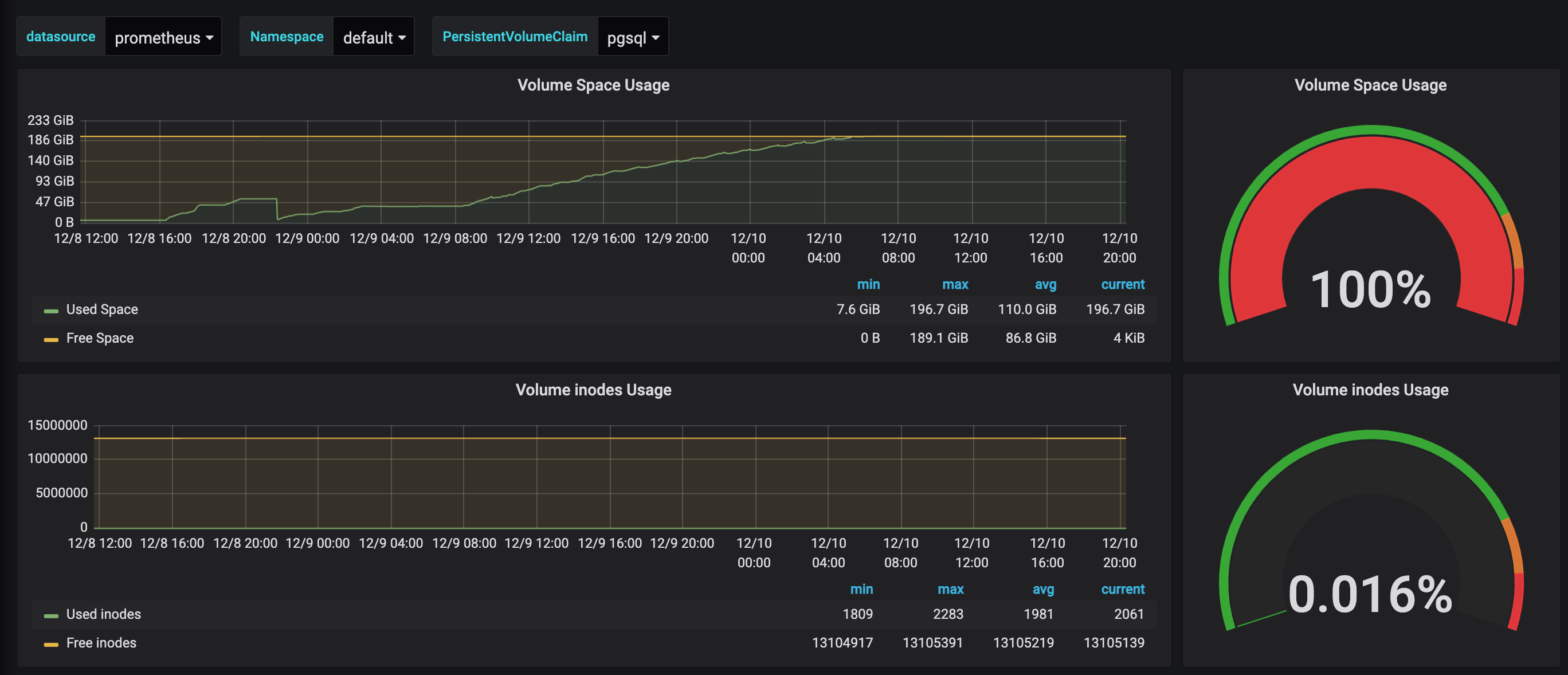

One of our large enterprise customers, who is also one of our earliest adopters of LSIF-based code intelligence at scale, had completed an upgrade from Sourcegraph 3.17 to 3.20. After the upgrade, they realized they were no longer getting refreshed precise code intelligence and sent us this cubist Sydney Opera House of a graph, indicating that something was deeply wrong.

The precise code intelligence worker process, which converts LSIF data uploaded by the user into our internal representation and writes it to our code intelligence data store, was ballooning in memory as jobs were processed. The extra memory hunger was extreme enough that the workers were consistently crashing with an “out of memory” exception towards the end of each job. No job was completing successfully.

After grabbing additional screenshots of our monitoring system, output to a few SQL queries, and a few pprof traces from the offending Go process, we proved that the culprit was the function that determined the set of uploads visible at each commit and knew we needed to find a way to reduce the resident memory required to do so.

To give a sense of this user’s scale:

- Their commit graph contained ~40k commits

- They had ~18k LSIF uploads scattered throughout the graph

- Over all LSIF uploads, there were ~8k known distinct root directories

While the commit graph itself was relatively small (the k8s/k8s commit graph is twice that size and could be processed without issue), the number of distinct roots was very large.

Memory reduction attempts

As an emergency first attempt to reduce memory usage, we were able to cut the amount of memory required to calculate visible uploads down by a factor of 4 (with the side effect of doubling the time it took to compute the commit graph). This was an acceptable trade-off, especially for a background process, and especially in a patch release meant to restore code intelligence to a high-volume private instance.

The majority of the memory was being taken up by the following UploadMeta structure, which was the bookkeeping metadata we tracked for each visible commit at each upload. The root and indexer fields denote the directory where the indexer was run and the name of the indexing tool, respectively. An index with a smaller commit distance can shadow another only if these values are equivalent.

| |

Two commit graph views must be created per repository: one traversing the commit graph in each direction. Each instance of an UploadMeta struct occupies 56 bytes in memory (calculated via unsafe.Sizeof(UploadMeta{})). At the scale above, these structs occupy nearly 30GB of memory, which excludes the values in the Root and Indexer fields. The values of the root field, in particular, were quite large (file paths up to 200 characters, the average hovering around 75 characters) and repeated very frequently. This was by far the dominating factor, as confirmed by the customer’s Go heap trace.

We replaced the struct with the following set of data structures, which yields a much smaller yet semantically equivalent encoding to the commit graph view defined above.

| |

The first change is the introduction of the Flags field, which encodes the data previously stored in the Distance, AncestorVisible, and Overwritten fields. We encode the value of the booleans by setting the highest 2 bits on the 32-bit integer, and keep the remaining 30 lower bits to encode the distance. This still gives us enough room to encode a commit distance of over a billion, which… if you’re looking that far back in your Git history I guarantee you’re going to get garbage out-of-date results. Now, the UploadMeta struct occupies only 16 bytes.

The second change is the replacement of the root and indexer fields by a map from upload identifiers to a hash of the indexer and root fields. Because we use these values only to determine which uploads shadow other uploads, we don’t care about the actual values—we only care if they’re equivalent or not. Our chosen hash always occupies 128 bits, which is a fraction of the size required by storing the full path string (75 characters take 600 bits to encode).

This also greatly reduces the multiplicity of these strings in memory. Before, we were duplicating each indexer and root values for every visible upload. Now, we only need to store them for each upload, as the values do not change depending on where in the commit graph you are looking. Logically, this was simply a string interning optimization.

Hitting a moving target

While we were busy preparing a patch release to restore code intelligence to our customer, they had upgraded to the next version to fix an unrelated error they were experiencing in Sourcegraph’s search code.

This made things far worse. In Sourcegraph 3.22, we moved the code that calculated the commit graph from the precise-code-intel-worker into the frontend in an effort to consolidate background and periodic processes into the same package. Our first stab at memory reduction wasn’t quite enough, and now the frontend pods were taking turns using all available memory and crashing.

This made their entire instance unstable, and this series of events escalated us from a priority zero event to a priority now event.

We attacked the problem again, this time by ignoring large amounts of unneeded data. When we pull back the commit graph for a repository, it’s unlikely that we need the entire commit graph. There’s little sense in filling out the visibility of the long tail of historic commits, especially as its distance to the oldest LSIF upload grows over time. Now, we entirely ignore the portion of the commit graph that existed before the oldest known LSIF upload for that repository.

In the same spirit, we can remove the explicit step of topologically sorting the commit graph in the application by instead sorting it via the Git command. This is basically the same win as replacing a sort call in your webapp with an ORDER BY clause in your SQL query. This further reduces the required memory as we’re no longer taking large amounts of stack space to traverse long chains of commits in the graph.

Our last change, however, was the real heavy hitter and comes in 2 parts.

Part 1: Using a more compact data structure

We’ve so far been storing our commit graph in a map from commits to the set of uploads visible from that commit. When the number of distinct roots is large, the lists under each commit can also become quite large. Most notably, this makes the merge operation between 2 lists quite expensive in terms of both CPU and memory. CPU is increased as the merge procedure compares each pair of elements from the list in a trivial but quadratic nested loop. Memory is increased as merging 2 lists creates a third, all of which are live at the same time before any are a candidate for garbage collection.

| |

We make the observation that looking in a single direction, each commit can see at most 1 upload for a particular indexer and root. Instead of storing a flat list of visible uploads per commit, we can store a map from the indexer/root values to the visible upload with those properties. Merge operations now become linear (instead of quadratic) in the size of the input lists.

| |

Part 2: Ignoring uninteresting data

We stop pre-calculating the set of visible uploads for every commit at once. We make the observation that for a large class of commits, the set of visible uploads are simply redundant information.

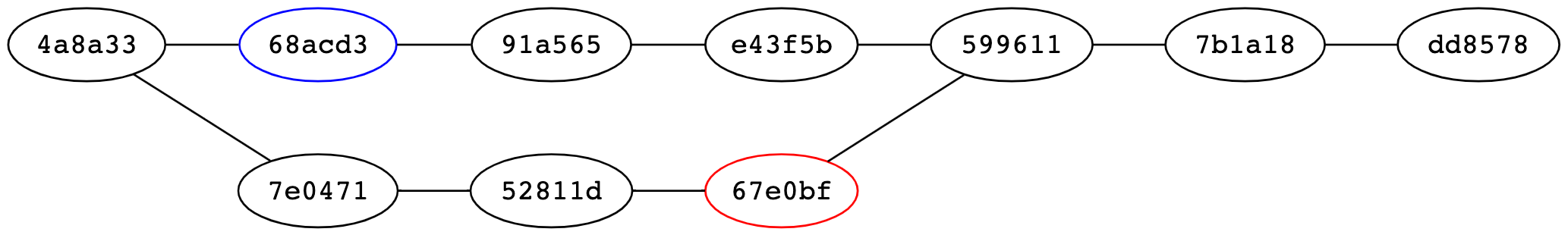

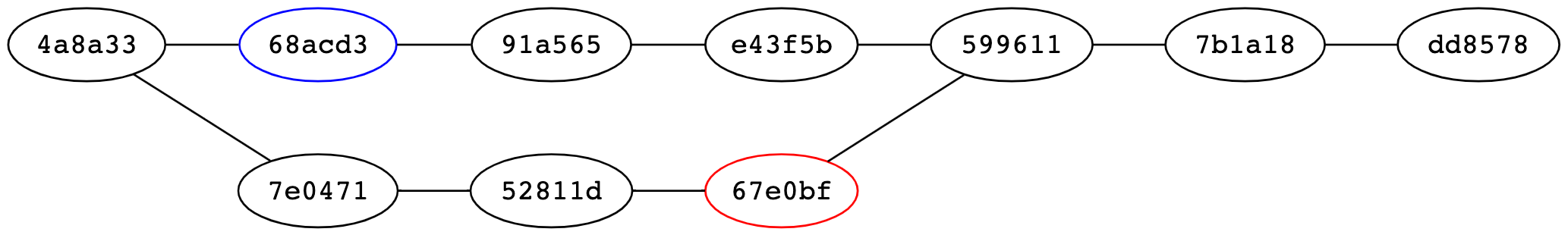

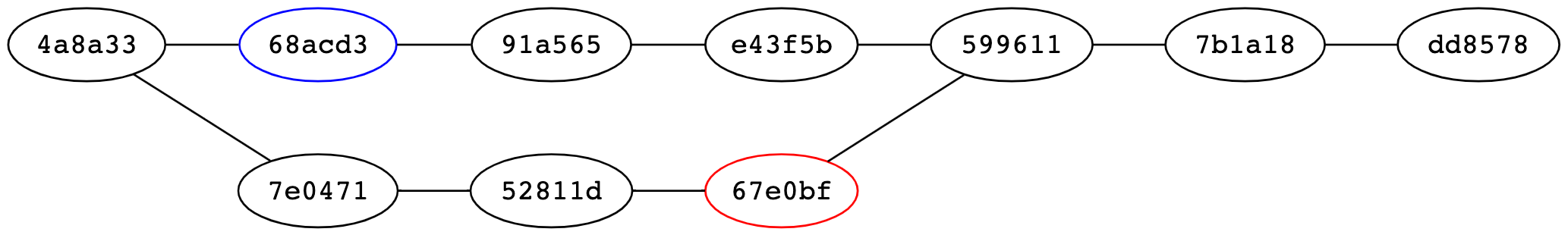

In the preceding commit graph, commits 91a565, 52811d, 7b1a18, and dd8578 are considered “trivial” and can be easily and efficiently recalculated by performing a very fast single-path traversal up the graph to find a unique ancestor (or, descendant in the other direction) for which we store the set of visible uploads. The re-calculated visible uploads are then the visible uploads of this ancestor with an adjusted distance.

The visibility for the remaining commits cannot be recalculated on the fly so easily due to one of the following conditions:

- The commit defines an upload,

- The commit has multiple parents; this would require a merge when traversing forwards,

- The commit has multiple children; this would require a merge when traversing backwards, or

- The commit has a sibling, i.e., its parents have other children or its children have other parents. We ensure that we calculate the set of visible uploads of these commits to make downstream calculations easier. For example, we keep track of the visible uploads for commit

e43f5bso that when we ask for the visible uploads from both parents of599611we do not have to perform a traversal.

It turns out that 80% of our problematic commit graph can be recalculated in this way, meaning that we only need to keep 20% of the commit graph resident in memory at any given time.

This last change turned out to be a huge win. When we started, the commit graph could only be calculated in 5 hours using 21GB of memory. Now, it takes 5 seconds and a single gigabyte. This is a ~3600x reduction in CPU and a ~20x reduction in memory.

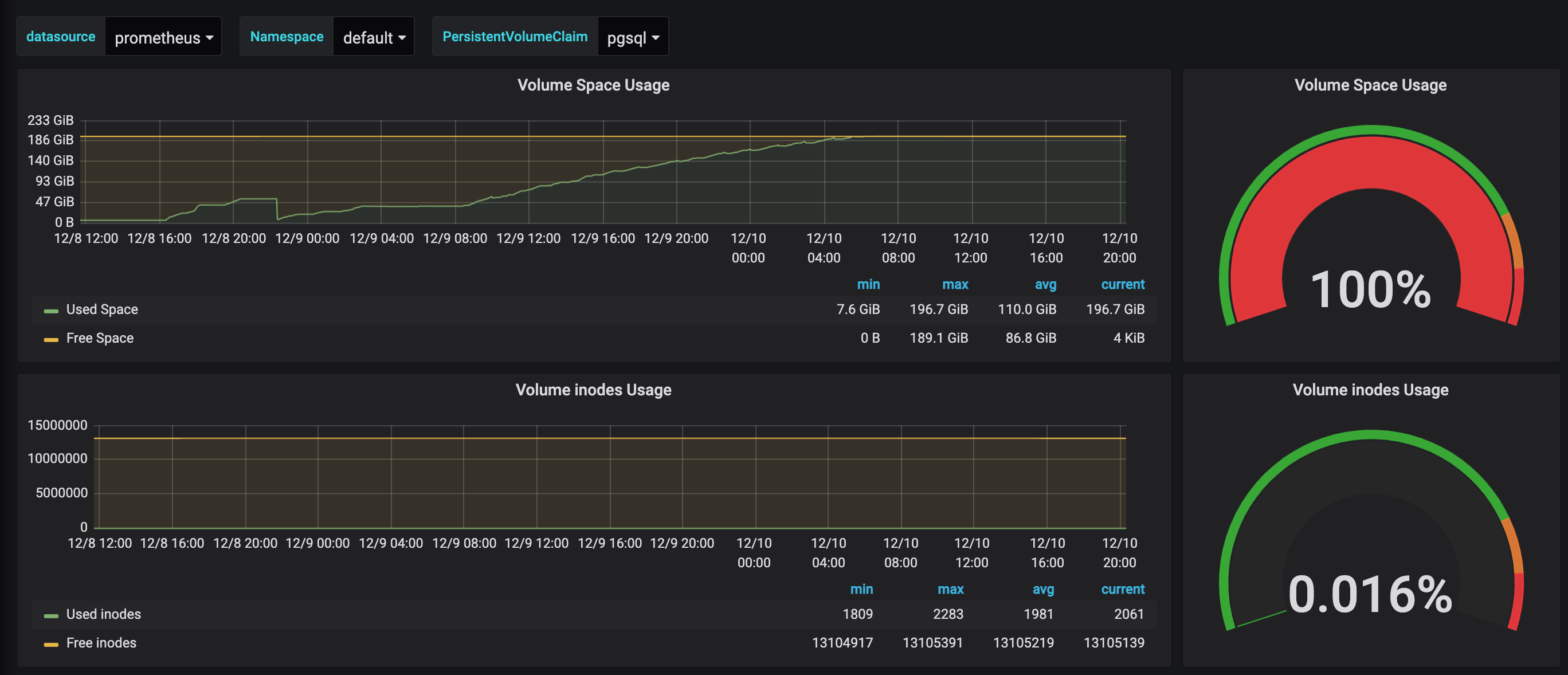

But of course the story isn’t over. We’re battling with the triple constraint of latency, memory, and disk usage here. And since we’ve optimized two of these properties, the third must necessarily suffer. Improvements in software often deal with similar time/space trade-offs. Removing a bad performance property of a system often doesn’t remove the bad property completely—it just pushes it into a corner that is less noticeable.

In this case, it was very noticeable.

Pick 3: low latency, low memory usage, low disk usage, or developer sanity

Home stretch—we can do this. To summarize:

- The speed at which we produce the commit graph is no longer a problem, and

- The resources we require to produce the commit graph is no longer a problem, but

- The amount of data we’re writing into PostgreSQL is a problem.

Our final and successful effort to fix these time and space issues attacked the problem, once again, in 2 parts.

First, we’ve changed the commit graph traversal behavior to look only at ancestors. Since we started to ignore the bulk of the commit graph that existed before the first commit with LSIF data, looking into the future for LSIF data now has limited applicability. Generally, users will be on the tip of a branch (either the default branch, or a feature branch if reviewing a pull request). We can still answer code intelligence queries for these commits, as they necessarily occur after some LSIF data has been uploaded. Additionally, an unrelated bug fix caused descendant-direction traversals to increase memory usage. So at this point, it just seemed sensible to stop worrying about this reverse case, which was never truly necessary from a usability standpoint. Looking in one direction reduces the amount of data we need to store by about 50%.

Second, we re-applied our tricks described in the previous section. We had good luck with throwing out huge amounts of data which we could efficiently recalculate when necessary, and save the resources that would otherwise be required to store them. This concept is known as rematerialization in compiler circles, where values may be computed multiple times instead of storing and loading the already-computed value from memory. This is useful in the case where a load/store pair is more expensive than the computation itself, or if the load/stores would otherwise increase register pressure.

Instead of writing the set of visible uploads per commit, what if we only store the visible uploads for commits that can’t be trivially recomputed? We’ve already determined the set of commits that can be easily rematerialized—we can just move the rematerialization from database insertion time to query time.

However, it’s not as easy as just throwing out the data we don’t need. We were previously able to rematerialize the data we didn’t store because we still had access to the commit graph from which it was originally calculated. To recalculate the values cheaply (without pulling back the entire commit graph at query time) we need to encode some additional bookkeeping metadata in the database.

We introduced a new table, lsif_nearest_uploads_links, which stores a link from each commit that can be trivially recomputed to its nearest ancestor with LSIF data. Queries are now a simple, constant-time lookup:

- If the commit exists in

lsif_nearest_uploads, we simply use those visible uploads, otherwise - If the commit exists in

lsif_nearest_upload_links, we use the visible uploads attached to the ancestor.

Example

We’ll use the following commit graph again for our example. Here, commit 68acd3 defines upload #1, and 67e0bf defines upload #2 (both with distinct indexing root directories).

The lsif_nearest_uploads table associates a commit with its visible uploads, just as before. But now, the number of records in the table is much, much smaller. The commits present in this table satisfy one of the properties described above that make the commit non-trivial to recompute.

| repository | commit | upload_ids |

|---|---|---|

| github.com/sourcegraph/sample | 4a8a33 | [] |

| github.com/sourcegraph/sample | 68acd3 | [1] |

| github.com/sourcegraph/sample | e43f5b | [1] |

| github.com/sourcegraph/sample | 67e0bf | [2] |

| github.com/sourcegraph/sample | 599611 | [1, 2] |

Luckily, some benefits compound one another here, and after we started ignoring traversing the graph in both directions, we can simplify these properties to only account for ancestor-direction traversals. Notably, commits whose parent has multiple children (7e0471, for example) no longer need to be stored because they were useful only in descendant-direction traversals (unless they are non-trivial for another reason). This further increases the number of trivially recomputable commits, saving even more space.

The lsif_nearest_uploads_links table stores a forwarding pointer to the ancestor that has the same set of visible uploads.

| repository | commit | ancestor_commit |

|---|---|---|

| github.com/sourcegraph/sample | 91a565 | 68acd3 |

| github.com/sourcegraph/sample | 7e0471 | 4a8a33 |

| github.com/sourcegraph/sample | 52811d | 7e0471 |

| github.com/sourcegraph/sample | 7b1a18 | 599611 |

| github.com/sourcegraph/sample | dd8578 | 599611 |

Note that for our instances with a large number of distinct indexing roots, this saves a massive amount of storage space. The majority of commits (> 80%) can link to an ancestor, which requires only referencing a fixed-size commit hash. The remaining minority of commits must explicitly list their visible uploads, of which there may be many thousands.

This set of changes finally reduces disk usage from 100% to a much more reasonable 3-5%. 🎉

And things seem to be remaining calm…

Lessons learned (part 2)

In Part 1 we pointed out that databases are a hugely deep subject and knowing your tools deeply can get you fairly far in terms of performance. Unfortunately, with the wrong data model, it doesn’t matter how fast you can read or write it from the storage layer. You’re optimizing the wrong thing and missing the forest for the trees.

In Part 2, we presented a fantastic way to “optimize the database” by reducing the size of our data set. Taking a step back away from the nitty-gritty details of an existing implementation to determine the shape of the data surrounding a problem can reveal much more straightforward and efficient ways to analyze and manipulate that data. This is especially true in a world with changing assumptions.