Jumping to the definition of a symbol under your cursor and finding all its references are two of the basic mental mechanics of software engineering. Fast code navigation accelerates the rate at which you can build a mental model of the code, and when it’s available, you’re likely to use it hundreds, if not thousands, of times per day.

Code navigation is the core of how Sourcegraph helps you understand the parts of the universe of code that are most relevant and important to you. Code navigation also presents a difficult technical challenge, especially when you want to provide code navigation outside the IDE in a variety of other applications where developers are trying to understand code: a web-based code search engine like Sourcegraph.com, private instances of Sourcegraph, and in code hosts like GitHub, GitLab, Bitbucket, and Phabricator through the Sourcegraph browser extension.

In order to provide compiler-accurate code navigation, IDEs work a lot of magic behind the scenes which involves static analysis, incremental compilation, build execution, and lots and lots of caching, much of which assumes read, write, and exec permissions on your local filesystem. So how does Sourcegraph provide precise code navigation to any user within milliseconds without this access? The answer is the Language Server Index Format, or LSIF (“elsif”). This post will share our technical journey with LSIF, including why we chose to adopt this as the foundation for our precise code navigation, the challenges we faced scaling an LSIF-based backend, and where we see things going from here.

Motivations

The journey to LSIF began in 2013 with the first version of Sourcegraph. Precise code navigation was a first-order concern, even in that early version of the application. At the time, code navigation was a feature that was available only in editors — and only in certain languages for each editor, depending on whether there was a plugin that added support for a specific language to a specific editor.

To enable code navigation in web-based interfaces (and with an eye toward enabling it across all languages in all editors), Sourcegraph created srclib, the first open-source cross-language code analysis toolchain and indexing format. Projects like the Language Server Protocol and Kythe were still years away from being released.

srclib worked quite well in those early versions of Sourcegraph. However, adding a srclib indexer for every language turned out to be quite an undertaking. There were many other product features that demanded time and attention, and so support for new languages was slow to develop. In the meantime, the Language Server Protocol emerged as a new open protocol for providing code navigation across many editors. LSP piggybacked on the growing traction of VS Code and many implementations of LSP emerged for most major languages. In this growing ecosystem, we at Sourcegraph saw an opportunity to take advantage of and also give back to an emerging open-source community that was dedicated to making code intelligence ubiquitous for every language.

We contributed language server implementations for Go, TypeScript and JavaScript, Python, and Java. And we incorporated language servers into our application architecture, so they could be deployed with Sourcegraph to provide precise code intelligence for many more languages that we had been able to provide with srclib and our limited developer-hours.

Language servers served our users well for a number of years, but eventually, as the amount of code on Sourcegraph.com grew and large organizations began to adopt Sourcegraph for their big internal codebases, scaling and performance became an issue.

Fast forward to early 2019, when our largest customer began regularly reporting language server outages related to high usage volume and large codebase size. We began looking for ways to improve performance at scale, and started thinking about how to combine the richness of the LSP ecosystem with the performance of an indexing-based approach like srclib.

In February 2019, to our surprise and delight, Dirk Bäumer, one of the creators of LSP, announced the Language Server Index Format (LSIF), a code intelligence indexing format “similar in spirit to LSP”.

What is LSIF?

LSIF provides a cross-language serialization format that describes the data needed to quickly resolve actions like go-to-definition and find-references. Raw LSIF data is JSON that looks like this:

| |

Sourcegraph accepts user-uploaded LSIF data, which can be generated by an LSIF indexer implementation in any local checkout of code. The most common scenario is as a step in a repository’s CI pipeline. Once Sourcegraph receives this data, it transforms it into an internal format, which is optimized for scale and query speed. Sourcegraph uses this data to power both local (with the same repository) and cross-repository code navigation actions like go-to-defintion and find-references.

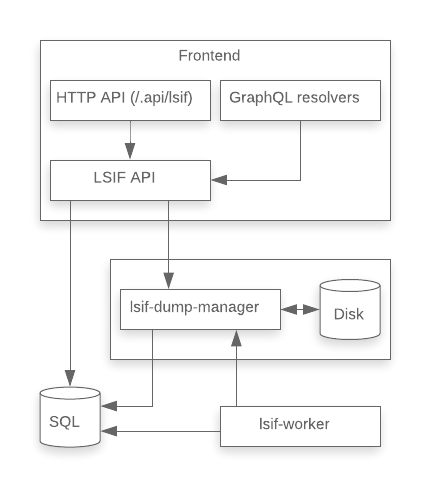

Today, the Sourcegraph LSIF backend has multiple components that each handle some aspect of uploading, parsing, transforming, reading, writing, and manipulating the LSIF data to serve user requests. This is the story of how this system grew and evolved over time. It is a story that spans 527 commits and +324k/-277k lines of code.

MVP

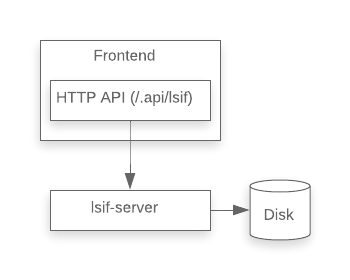

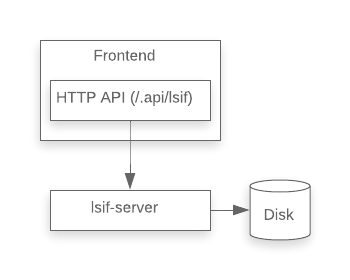

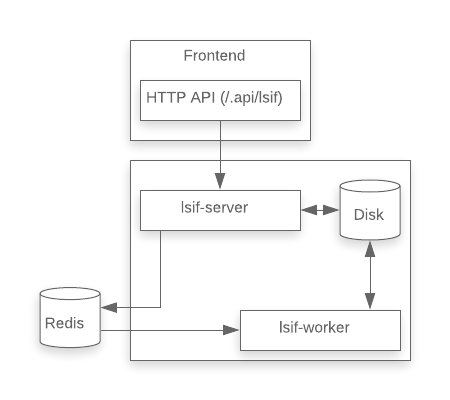

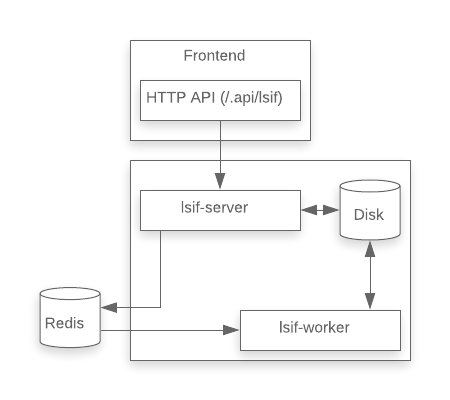

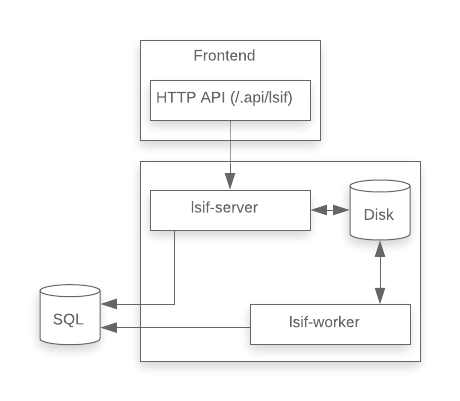

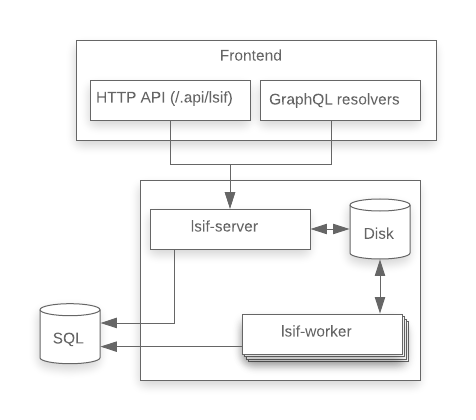

The LSIF backend began life as a simple Express server written in TypeScript, proxied to the outside world by an endpoint in the Sourcegraph frontend API. This server accepted LSIF uploads and wrote them directly to disk. On a query request, the server would read the LSIF data for the current repository from disk into memory, parse it into a structured representation, and walk the graph of vertices and edges to construct the appropriate response.

On the client side, we wrote a simple Sourcegraph extension to query the lsif-server API.

We chose TypeScript and Express, because this was the fastest way to get something up and running, given the experience of our team. The primary goal was to solicit feedback from users about the ergonomics of the upload API (for which users would have to configure their CI pipeline to generate LSIF) and the basic user experience of code navigation backed by LSIF. Performance, scalability, robustness, and code quality were not primary concerns.

Optimizing for queries

To serve queries, the MVP implementation would simply read the raw LSIF data from disk into memory, parse it into a structured representation, and then walk the graph to compute the query result. LSIF indexes, however, can be very large (larger than the size of the codebase at any given revision). On larger codebases, this added significant latency to serving the user request and would often also call OOM crashes.

We needed to make the following operations fast:

- get definitions for an identifier at a given source position

- get references for an identifier at a given source position

- get the hover text for an identifier at a given source position

In order to do this, we decided to store the LSIF data in a different format that was optimized for these operations. After several design discussions, we reduced our choices to two options:

- SQLite, an embedded file-based SQL database engine, and

- Dgraph, a distributed graph database built on top of an LSM-tree-based database BadgerDB.

We built two versions of the backend. Benchmarks showed that the upload performance of the SQLite and Dgraph backends were both proportional to the input size: SQLite with a factor between 2.2x and 2.8, and Dgraph with a factor of 25x. We were relatively inexperienced with Dgraph, so the relatively slow performance could be explained by a lack of operational experience and a bad choice of graph schema (the Dgraph backend implementation can be found here).

Had we more time, we might have experimented more with Dgraph, but we decided to go with SQLite based on its higher initial performance, the familiarity we had with using it in the past, and the fact that it would be easier to deploy operationally into the many deployment environments that our customers have.

After this change, queries only needed to read from disk the documents containing the target source range, instead of the LSIF dump for the entire repository.

Processing uploads asynchronously

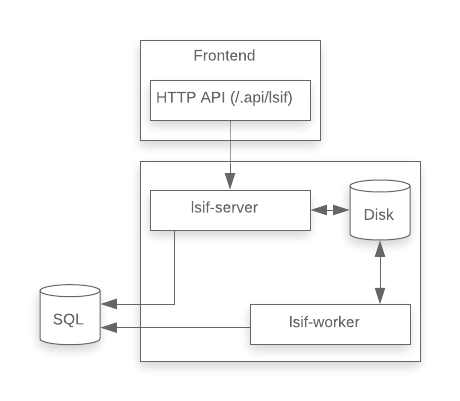

In the MVP, the LSIF upload process was synchronous. This was acceptable in the MVP, because all it was doing was reading the LSIF data from network and writing it directly to disk. Adopting SQLite as the backend store for precise code navigation added an additional transformation step to the LSIF upload process. Rather than simply read the LSIF data from network and write directly to disk, we now had to parse the data and convert it into a SQLite bundle. This increased the LSIF upload response time significantly, and we began bumping into timeouts enforced by various clients, servers, and proxies within or around Sourcegraph.

We also started to see more frequent OOM errors in the lsif-server process for larger uploads, as the data conversion process also increased memory usage. The same process handled both uploads and queries, so uploading a large file (or multiple small ones in parallel) could, by OOMing the process, also take down code navigation queries.

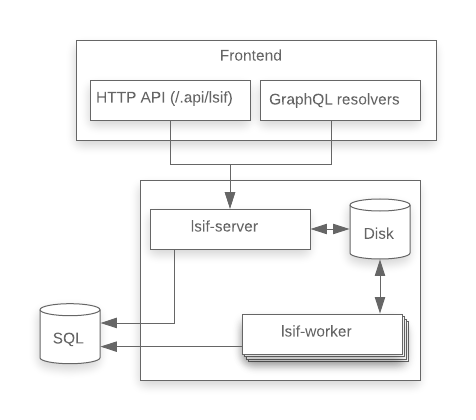

To address this issue, we decided to separate the work of converting LSIF into SQLite bundles into a separate background process. The lsif-server process would continue to handle uploads and queries, but the uploads handler would be similar to that of the MVP implementation, transparently writing the raw data to disk rather that converting it synchronously. The lsif-worker1 process would consume the queue of LSIF dumps to process, converting these to SQLite bundles in the background.

To coordinate work between the LSIF upload handler and the lsif-worker process, we needed a queue. We used node-resque, a Node.js port of the popular Rails library resque. This library stores job data in Redis, which was already a component of our stack. We also considered using PostreSQL (but accessing the existing PostgreSQL instance came with certain restrictions due to concerns for uptime and performance), some sort of local IPC (but this would have prevented scaling lsif-server and lsif-worker independently), and using an AMQP server (but this would have required introducing a new major service into our architecture).

We implemented the splitting of lsif-server and lsif-worker in this PR.

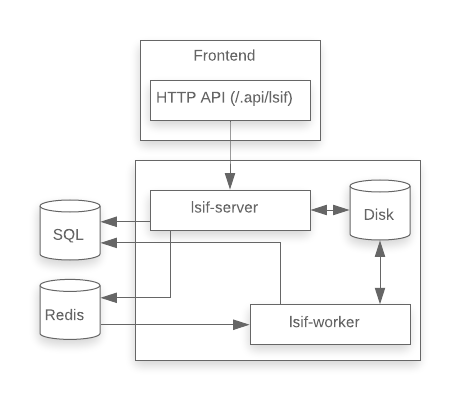

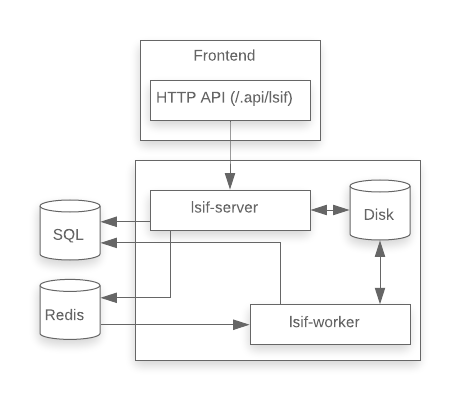

Storing cross-repository data in PostgreSQL

Each uploaded LSIF index became a single SQLite database on-disk. These single-repository databases would have been sufficient to support local (within the same repository) code navigation. In order to make the code navigation experience truly seamless and magical, we wanted to support cross-repository code navigation. In other words, we wanted users to click on a reference to a function defined in some dependency and arrive directly at the definition of that function in its source repository. Pretty neat!

To enable that, we added an additional SQLite database (xrepo.db) that enabled us to look up repository indexes by the versioned packages they provided and the version packages on which they depended.

This was fine so long as there was just one instance each of lsif-server and lsif-worker and they both lived in the same Docker container. However, in order to support LSIF across large, multi-repository codebases, we needed to scale. This meant that the multiple lsif-server and lsif-worker instances would be running in different Docker containers, perhaps on different machines, and could no longer rely on share access to a single-writer-at-a-time SQLite database. We moved the xrepo.db data into PostgreSQL.

The potential volume of additional writes continued to concern us. As LSIF use grew, would it cause operational issues in the PostgreSQL instance that would affect the performance of unrelated parts of the application? To be safe, we kept the table spaces of the LSIF data disjoint (prefixed table names, no foreign keys to existing tables) from the other data. We also tried migrating the LSIF tables into a second PostgreSQL instance. However, this required some nasty trickery with db_link in order to run migrations, which we found quite painful and eventually reverted. Some more back-of-the-envelope calculations suggested that the LSIF-related load wouldn’t overwhelm the single shared PostgreSQL instance, and these calculations have largely held up over time.

Queue v2: Bull and Redis

We saw some operational issues related to stuck workers and lost jobs that we traced back to our queueing library, node-resque. This motivated a switch to Bull, which also had some additional features that allowed us to schedule jobs (similar in spirit to cron), list all jobs in a particular state, and search within job payloads for text matching a query using Redis’s EVAL command.

The relevant PRs:

- Replace node-resque with bull (#6062)

- Add machinery for repeated/scheduled jobs (#6067)

- Add scheduled job to clean old job data (#6136)

- Endpoints for jobs in lsif-server (#6227)

Queue v3: PostgreSQL

The adoption of Bull resolved some issues in our queue implementation, but others remained. In particular, there was a problem of enforcing logical transactions across data that was stored partially in Redis and partially in PostgreSQL.

In particular, data could be written to PostgreSQL indicating the successful completion of an LSIF bundle conversion, but the corresponding job in the queue, stored in Redis, could not be updated within in the same transaction. These sometimes got out of sync.

Furthermore, Redis is treated by other parts of Sourcegraph as an ephemeral and truncatable cache. Site administrators were aware of this, and if they felt they could safely wipe Redis data, this would wreak havoc on the LSIF processing queue.

To address these issues, we moved the queue data from Redis into PostgreSQL. This reduced a lot of complexity. As it turned out, all of the custom Lua scripts that reached into the Redis data could be reduced into a few SQL queries. We could now also use PostgreSQL transaction to enforce all-or-nothing atomicity on LSIF-related updates.

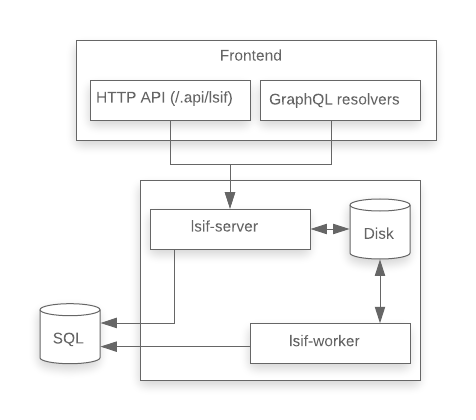

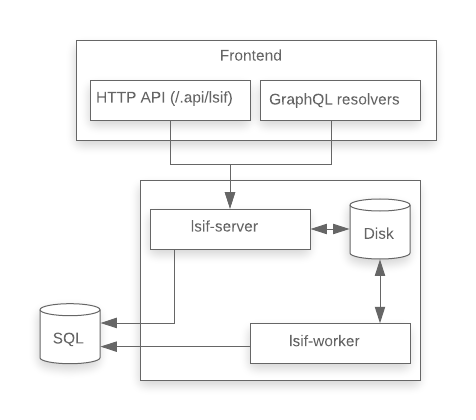

Adding GraphQL resolvers

For a while, the lsif-server was accessible only through an undocumented proxy in the Sourcegraph frontend service. This proxy accepted uploads and served code navigation queries. The only consumers of this API were first-party Sourcegraph extensions like sourcegraph/go and sourcegraph/typescript.

Adding a GraphQL API enabled the LSIF backend to be used by other parts of Sourcegraph, such as the nascent Batch Changes feature, and also to third-party Sourcegraph extension authors and third-party API consumers. As the functionality of the LSIF backend continues to grow (we’ve recently added support for diagnostics), so do the possibilities for users of this API.

Introducing multiple workers

The lsif-server and lsif-worker were still run together in the same container. As an easy way to enable multiple workers without changing the container orchestration, we decided to prefork the worker.

This was a rudimentary way to scale, as overall resource use was still constrained by the single container and there was no isolation between worker processes (meaning runaway memory use in one can starve out all the others in the container), but this worked well enough for the time being. This change also helped us resolve some issues with LSIF processing on Sourcegraph.com, which was suffering from head-of-line blocking.

Introducing the bundle manager

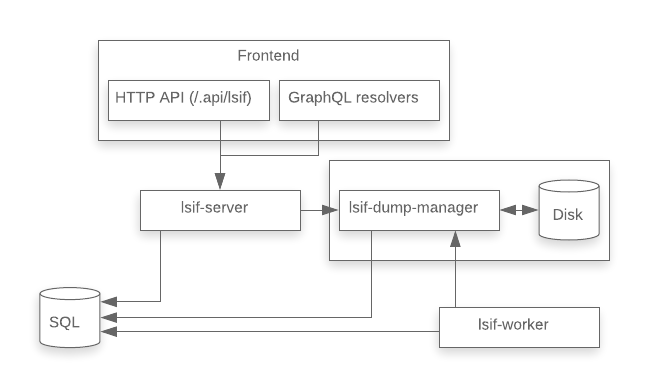

We needed to enable the lsif-server and lsif-worker instances to scale horizontally. At the same time, all instances had to have shared access to the same persistent storage that would store the LSIF data used to serve queries.

Naively, we thought this might be possible by simply attaching a shared disk to each separate instance. In practice, however, there are some issues with doing this. Kubernetes Persistent Volumes by default cannot be mounted as read-write-many across multiple nodes. There are volume plugins such as CephFS, GlusterFS, and NFS that enable this, but the reliability and performance of such shared access filesystems can be an issue and furthermore, they were unsupported in GCP, which is what Sourcegraph.com is deployed on.

The solution was to factor out the responsibility of managing the shared storage into a separate service, the bundle manager (originally called the lsif-dump-manager, today known as the precise-code-intel-bundle-manager).

This made the lsif-server and lsif-worker stateless, freeing them to scale horizontally. Scaling the bundle managers requires a sharding scheme, similar to what we already used for the gitserver service that is responsible for serving Git data in the Sourcegraph backend.

Rewriting in Go

The original LSIF backend had been written in TypeScript, because that was easiest to prototype and it also matched the technical skillset of the original team. Over time, performance became more of a consideration and the experience of the team shifted more toward Go. In particular, we were familiar with a variety of techniques to optimize programs written in Go, but were less well-versed in such techniques for applications written in TypeScript.

Because performance was becoming a first-order consideration, we decided to rewrite things in Go.

Initially, we decided to adopt the strangler fig model of refactoring, extracting first only the CPU-bound work into a high-performance Go process, which would be called by the existing worker code. Eventually, over time, more of the logic would be ported into the Go process.

However, things don’t always go according to plan.

I knew the ins and outs of the TypeScript code, so I simply rewrote all three services in Go in a single pass. The resulting code wasn’t particularly idiomatic, since I wanted to focus on bringing the new system to life as quickly as possible, so we could sunset the old one. Continuing refactors have made the code more idiomatic over time.

The rewrite has unlocked a large number of performance improvement opportunities, the results of which are described in Optimizing a code intelligence backend.

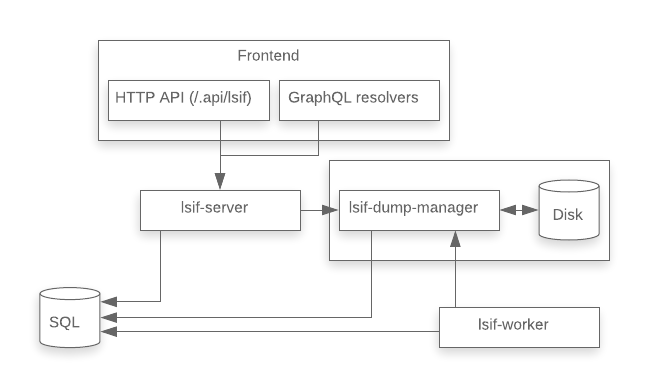

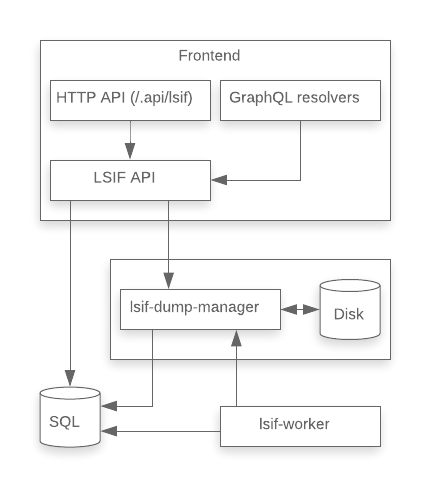

Removing lsif-server

After rewriting the LSIF backend in Go, the LSIF API server (lsif-server) was completely stateless and it no longer had to talk to a process (the bundle manager) written in a different language. After taking a step back, we realized the API server process now had little purpose.

We moved what remained of the LSIF API server logic from the server handlers into the client used by other parts of Sourcegraph (the external HTTP and GraphQL APIs) to query LSIF data. Then we dropped the LSIF API server:

Looking forward

The journey isn’t stopping here. In 3.17, we made significant performance improvements to the LSIF backend, and we will continue adding features and investing in optimizations to support massive scale for LSIF.

Just a few things we are looking forward to:

- Automatic, zero-config LSIF indexing of repositories

- Support for monorepos and other large repositories with high commit frequency

- Creating a public index of all open-source code, and connecting this to private code to enable seamless jumping from proprietary code to open-source dependencies

Keep an eye out for updates!

The lsif-worker process is today known as the precise-code-intel-worker. ↩︎