Within the rapidly expanding domain of artificial intelligence, the capacity for Large Language Models (LLMs) to sift through extensive codebases and provide insightful responses has evolved into a critical necessity for today’s software developers. The traditional search methodologies have proven insufficient time and again, as developers find themselves spending countless hours grappling with them, only to be left navigating through a labyrinth of misleading results, hallucinations and vague responses to their code-related inquiries.

For LLM based coding assistants to live up to their potential and solve these problems, they need to have the best possible context. Here’s what we’re doing to take the context Cody already has and make it even better.

Orthogonal search dimensions

Embeddings-powered search indexes are constructed by reducing the input corpus into a semantic vector space. Reductively, when two documents cover similar ideas, they would appear within this vector space close together. To retrieve documents related to a particular keyword, those keywords are also translated into the same vector space, and the documents closest to the keywords are considered candidates for retrieval. DataStax has a good primer on the subject.

By default, Cody gets context solely using embeddings.

Think of embeddings-powered search as an excellent tool for addressing broad, high-level inquiries. For instance, when you pose a question about authentication, it naturally seeks to incorporate pertinent documents related to this topic. However, when the query shifts to implementation specifics of a certain code, the expansive, overarching ten-thousand foot view perspective isn’t as effective. That’s where our vast repository of compiler-accurate source code indexes comes into play.

SCIP allows us to navigate the semantic relationships between different code snippets, including the most relevant ones within the context window. As a result, we gain a detail-oriented source view of the same data, enabling us to provide more granular context with precision.

In the course of using LLMs to develop coding AI assistants, we’ve been met with the hard problem of taming what the industry has coined “hallucinations”. Our initial attempts at dealing with hallucinatory responses were to detect, tag, or otherwise filter the portions of responses that were generated purely via probability rather than any apparnet understanding of the code under discussion. We’ve since discovered that providing the proper initial context, and preventing the generation of incorrect information completely, is the optimal way to deal with such hallucinations.

Let’s make our case with a few examples.

Risperidone

As it turns out, the greatest LLM anti-psychotic is giving it enough of the correct context in the first place.

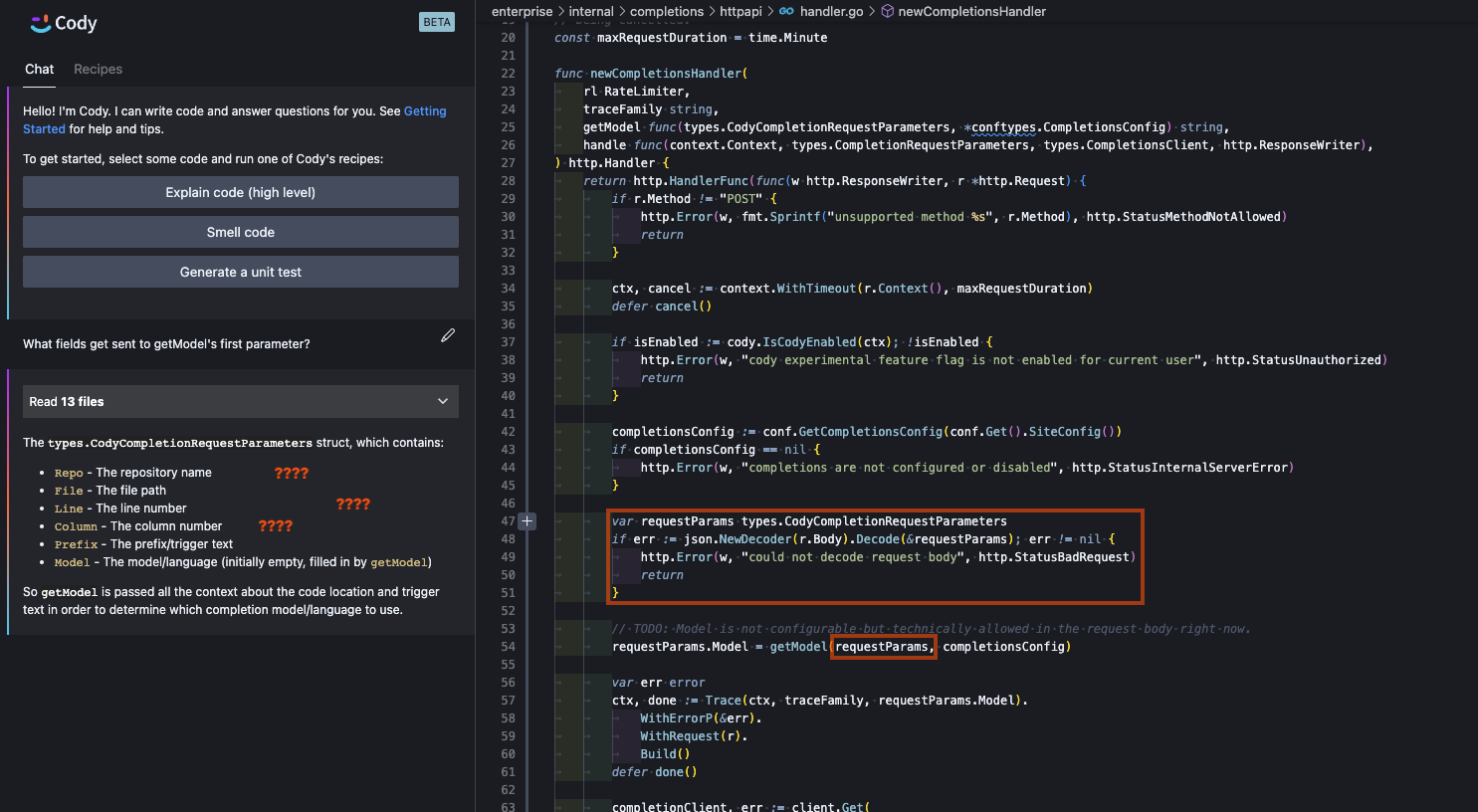

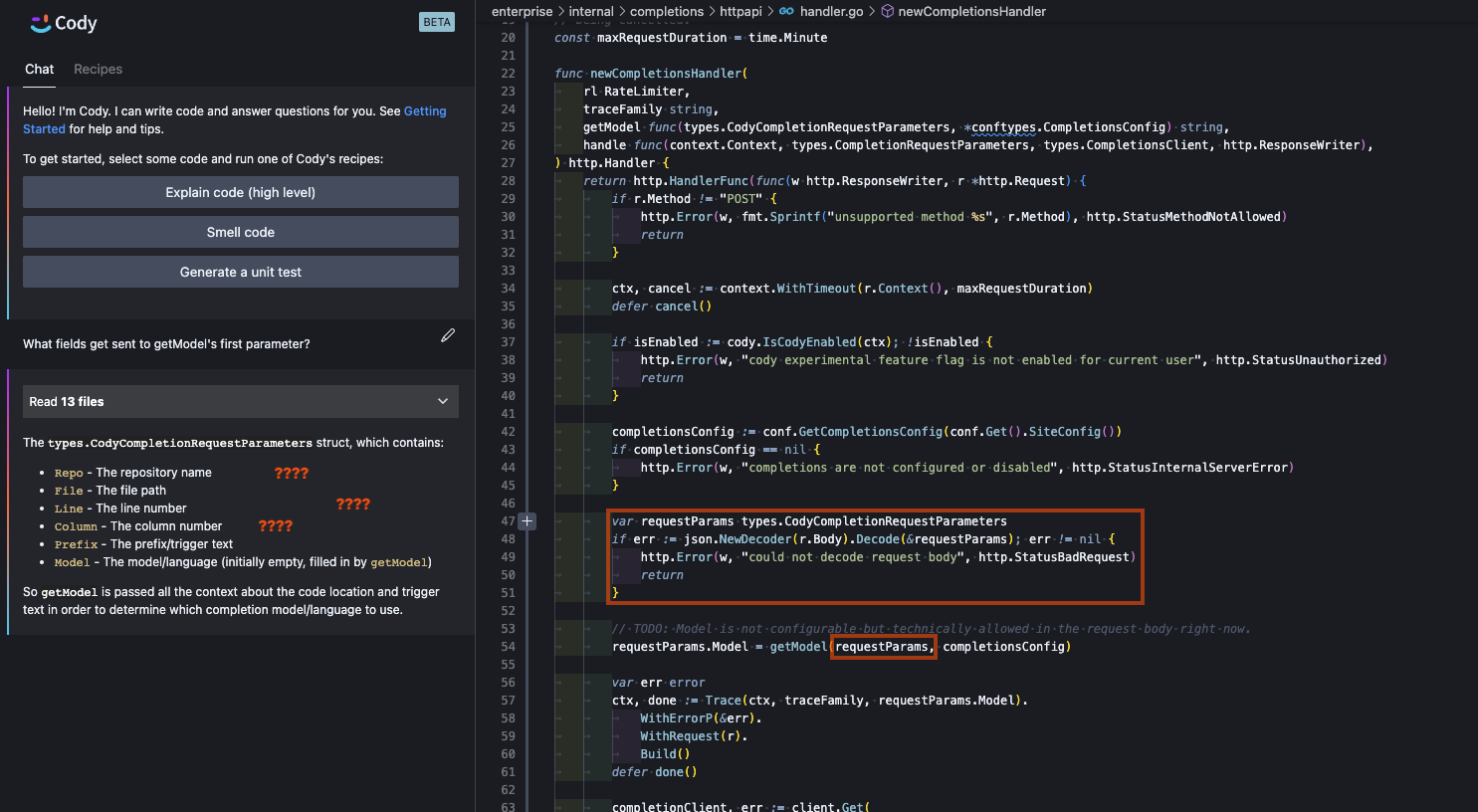

Cody, without tapping into the power of precise code intelligence, does a good job of understanding the semantic meaning of code - at least when it’s visible to the underlying LLM. In the following example, we ask for a list of fields sent to an invocation of a function. Cody understands the the question entirely and gives a completely valid response, even correctly indicating that parameter we’re discussing has the type types.CodyCompletionRequestParameters.

Unfortunately, while Cody gets the parameters correct, the fields listed in Cody’s response aren’t the actual fields of the types.CodyCompletionRequestParameters struct. They’re just what Cody would assume these fields to be without having the shape of the type readily present in its training data or context. This struct, in reality, contains the fields Prompt, Messages, MaxTokensToSample, Temperature, StopSequences, TopK, TopP, Model (embedded under a named struct), and Fast. The hallucinated fields produced by Cody have zero overlap with this type, although we can recognize some red herrings from the surrounding code that it seems Cody followed to produce a best-guess (and confident) response.

These types of hallucinations can be particularly frustrating, as they aid in building an incorrect mental model for the developer of the code that later needs to be torn down and rebuilt. Responses that are correct at-a-glance can lull users into a false sense of security.

Why the discrepancy? Well, ‘Stock Cody’ is powered by searching for code similar to the content of your question. And this works really well for questions pertaining to high-level questions about code (“How do we handle auth in service X?”), but doesn’t perform as hot when sufficient answers would require a traversal of the code (“Are there concurrent uses of this variable?”). Our question above is asking for such a highly precise answer related to a specific piece of code. It requires more than a vague sense of what the code accomplishes - it needs to know how it accomplishes it as well. For such implementation-specific questions, we need to be able to explore a different relationship within the code graph.

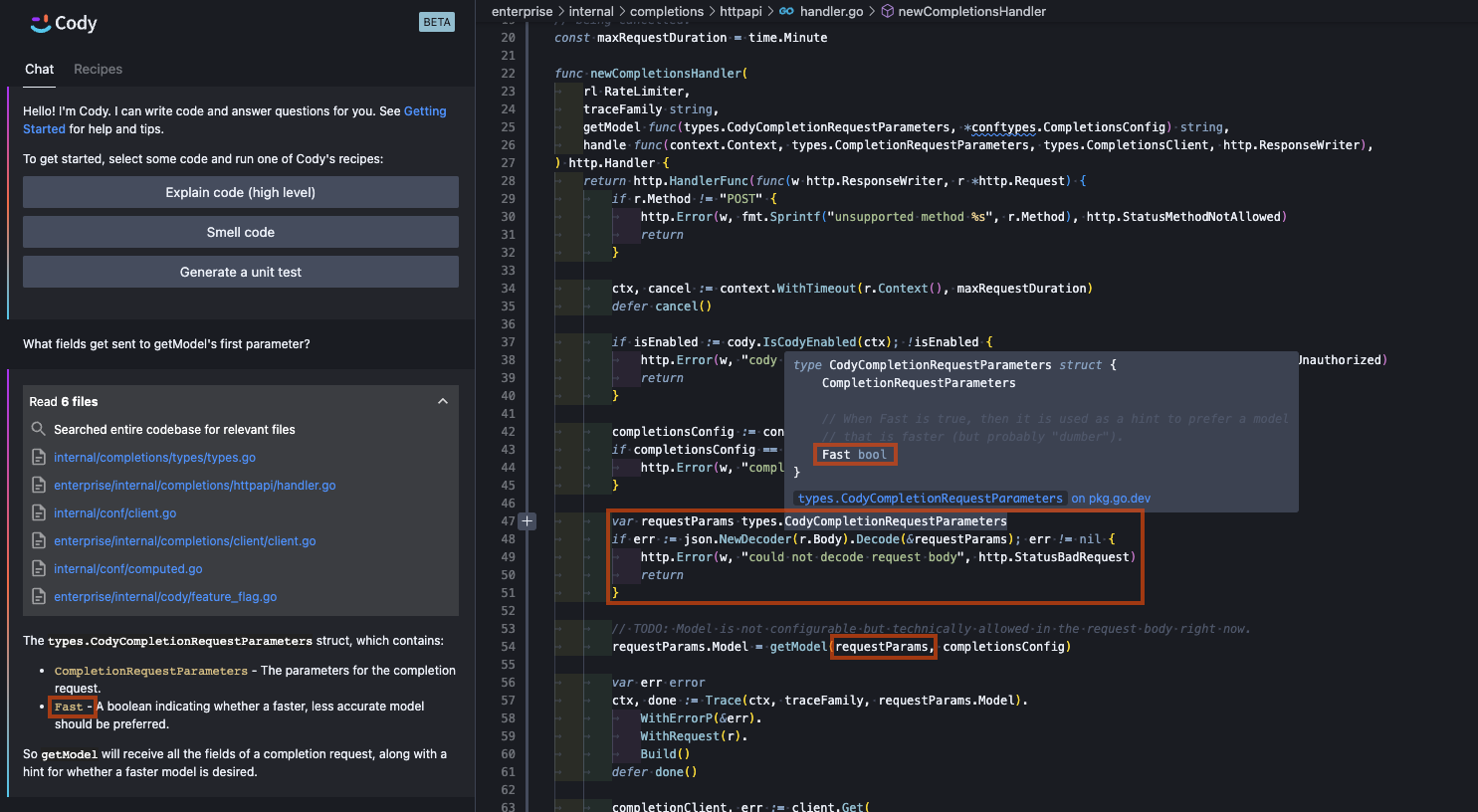

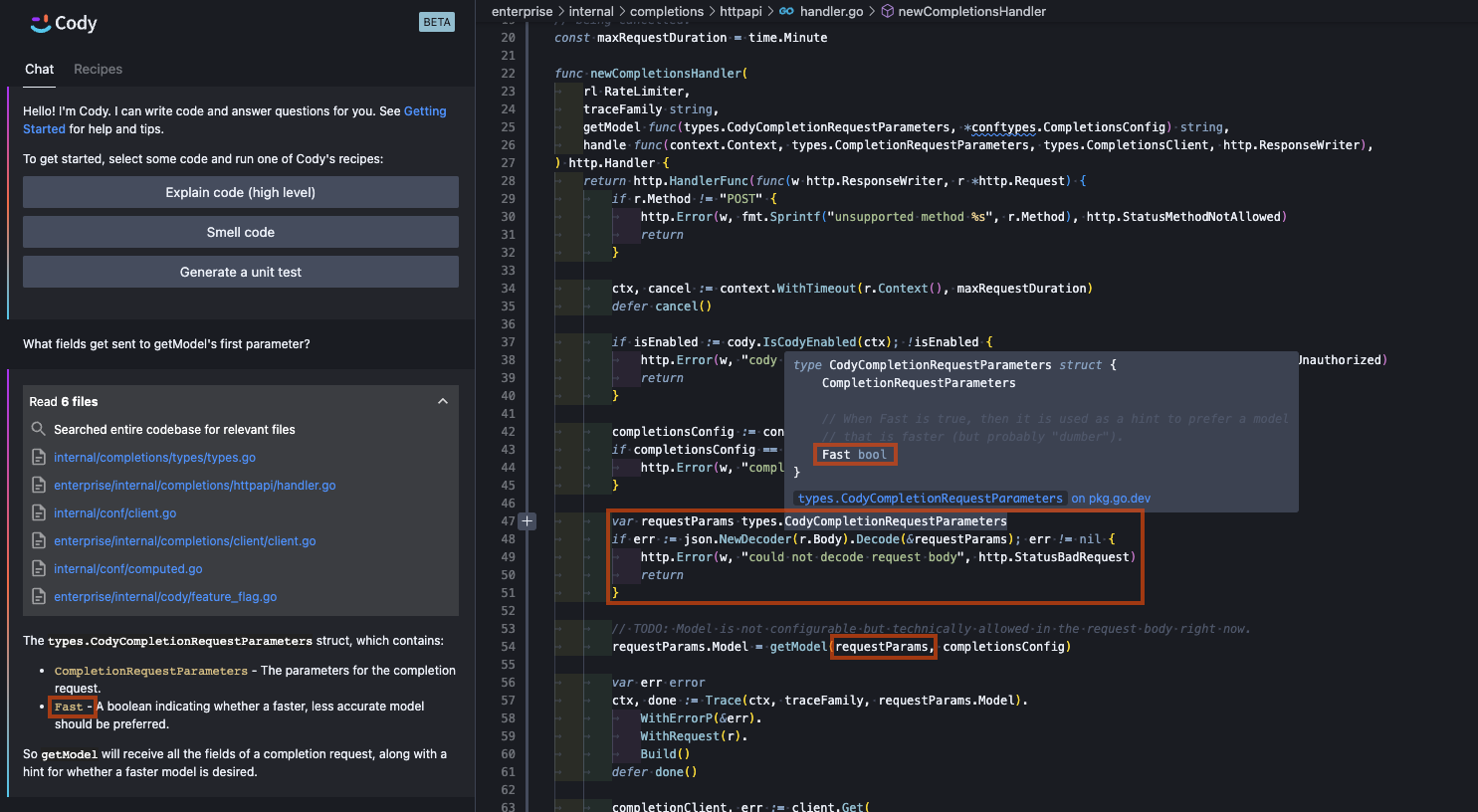

For the same question, we can improve Cody’s response by supplying additional code we find traversing the definition edges of the semantically-indexed portion of the code graph. To start the search, we extract symbol names from the code that is currently in the view of the user, such as the current workspace, the user’s text selection, open files, etc. These symbol names are translated into a location in our SCIP backend. Then, particular edges are followed out to explore the graph. As we traverse the graph in this manner, we recall code that is semantically related to the code in question.

Including the definition (hence the concrete field names) in the LLM context window provides enough information to effectively prevent the spew of probable-but-fallacious field names we got when it had no concrete examples in its working memory. (Note that we’re no longer hallucinating fields, but do not expand all fields present in a traversal; we’re currently only performing single-edge traversals but plan to expand the search space in the future.)

In the land of infinite possibilities…

Generative AI gonna generate.

Too many answers are valid when too little context is given to restrict the solution space. This is a special form of garbage-in, garbage-out. As a reaction to this behavior, users of LLMs have learned to attach a qualifying prefix to their conversations, such as “assume I’m a senior software engineer” or “pretend you’re my L5 peer at a FAANG.”

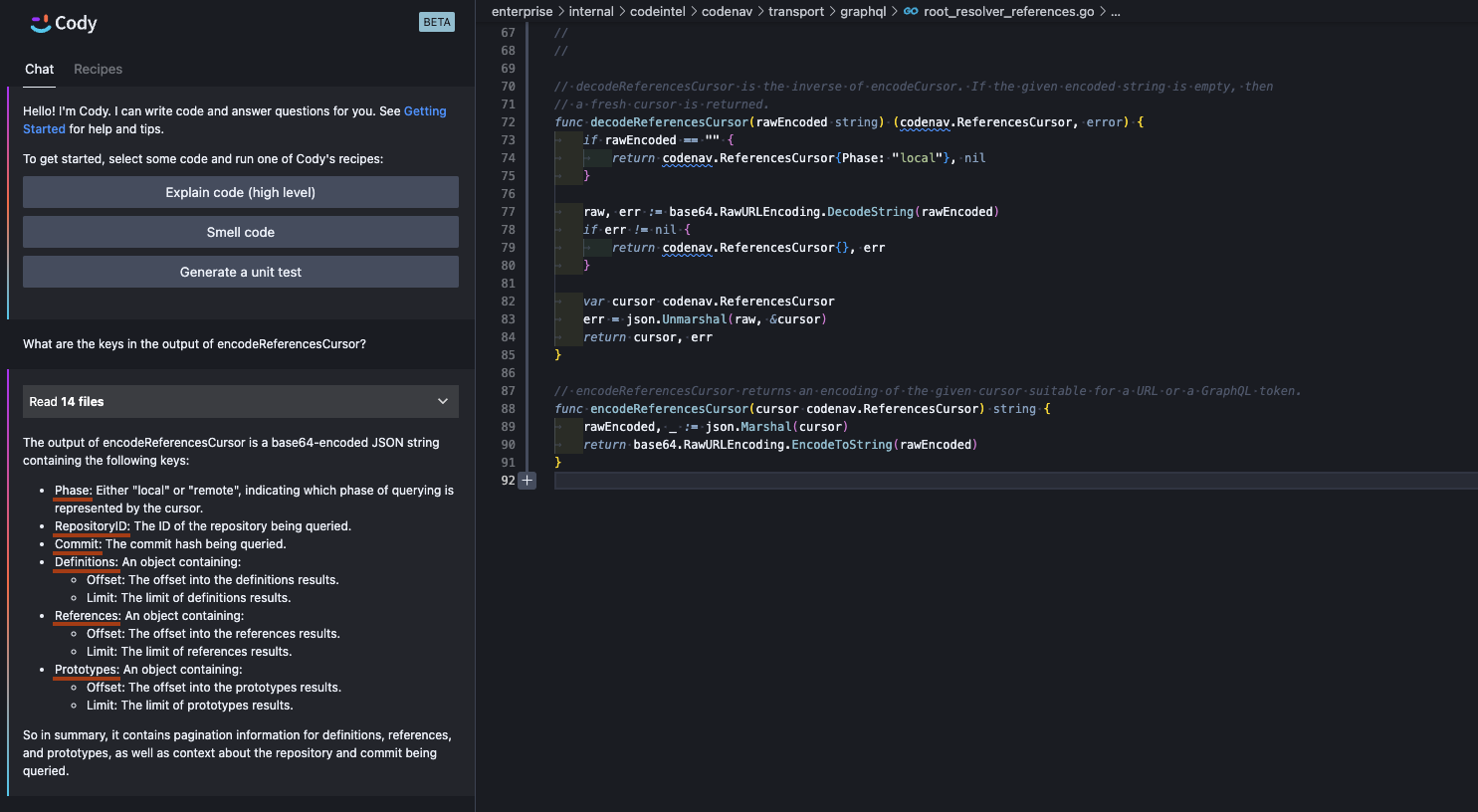

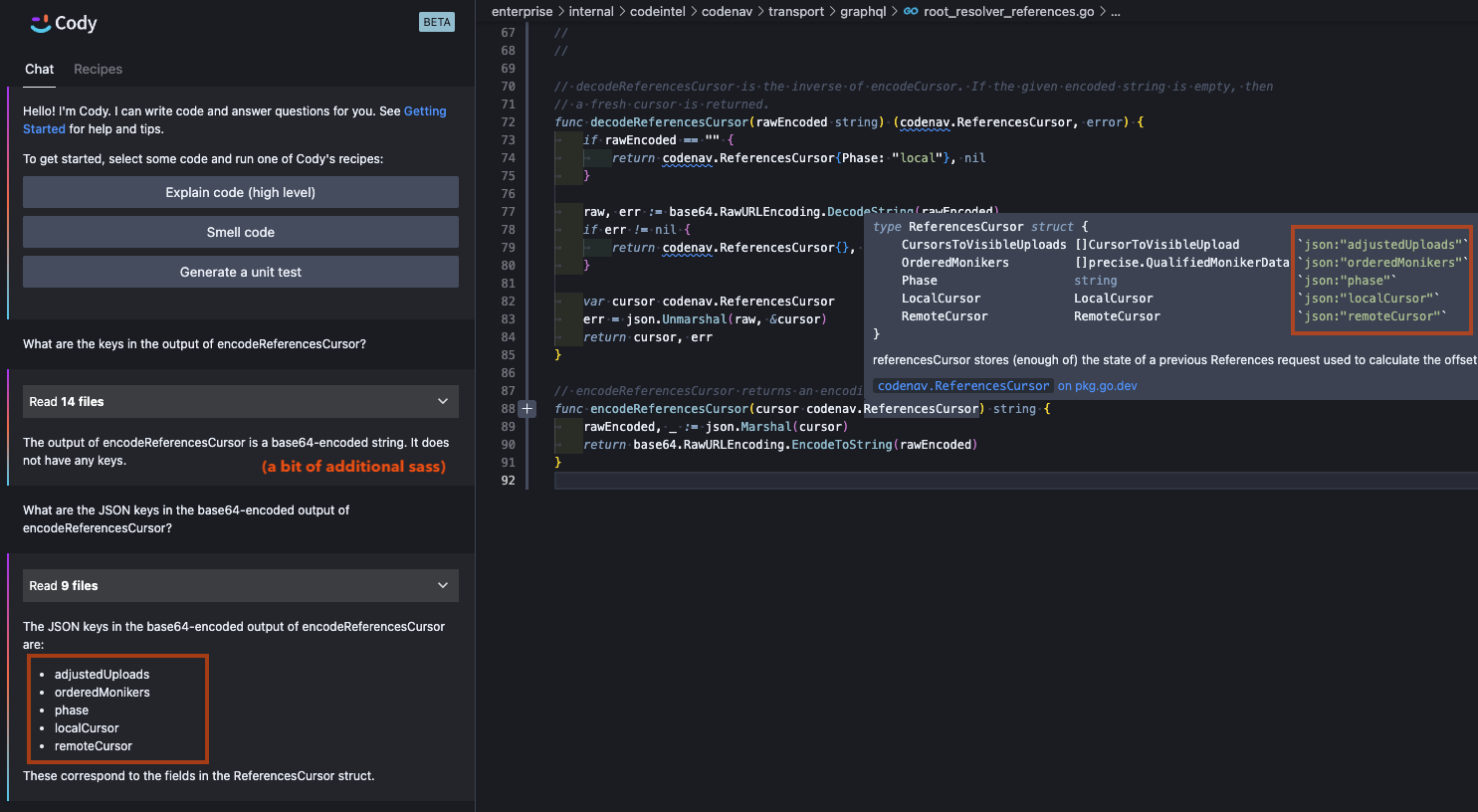

In the following example, we ask Cody to describe the output of a particular function when executed. We choose this particular example in which the input question has little to no similarity to the internal implementation of the function to ensure embeddings search alone would not return all of the relevant context.

Luckily, embeddings search alone often includes a lot of the critical context to make magical-seeming inferences. In this example, the description of the cursor is correct as the embeddings search retrieved the related GraphQL schema file, as well as some other files in the same package which by happenstance also make use the cursor object. This is why the Phase field is known to have the values "local" and "remote". All of this is spot-on, although oddly the value "done" is not explicitly listed as a possible phase even though it visible in the source of the screenshot above.

The remainder of the response slips wholly into hallucination territory. While RepositoryID and Commit do not actually exist in the cursor, similar fields do exist on a sibling RequestArgs struct that’s passed around many of the same code paths. This is likely a source of the confusion in the response. The three remaining fields, Definitions, References, and Prototypes, do not exist on the cursor, but they do make remarkable sense given the context of the code in which this cursor is being used. These fields could absolutely be a valid alternate design for an API in the same domain. But it’s not the design of the code we’re discussing.

Generative AI is simply a machine that finishes a pattern. If sufficient examples are not available to narrow which pattern to follow, it seems that anything can come shooting out. An AI coding assistant that always responds with the know-it-all answer of “you could’ve designed it this other way” is not only unhelpful, but enraging to hear. Especially if you’ve previously fallen for AI-powered refactor suggestions and the other way is how you originally wrote it!

We can sufficiently narrow down the pattern-space by supplying additional highly relevant code into the context. With enough of the right context, answers will adapt themselves to the environment, rather than making leaping inferences about the environment to support its output. Supplying this additional context bounds the valid output space so that these hallucinations no longer occur.

Deeply understanding code

The skeptical reader may have noticed a heavy similarity between the first two examples - both questions are basically using an AI layer to emulate a fairly simple jump to definition action. Asking these questions in natural language probably takes more time than hovering over the symbol to peek at its definition. These examples are highly illustrative but also very myopic with respect to what’s possible with this technique.

Precise code intelligence is far from a one-trick-pony source of context.

Cody should have the capability to detect bugs and suggest improvements given enough context to sufficiently understand the code it’s analyzing. Today, Cody will try its best to suggest improvements, but remains confidently ignorant of any context it wasn’t explicitly fed.

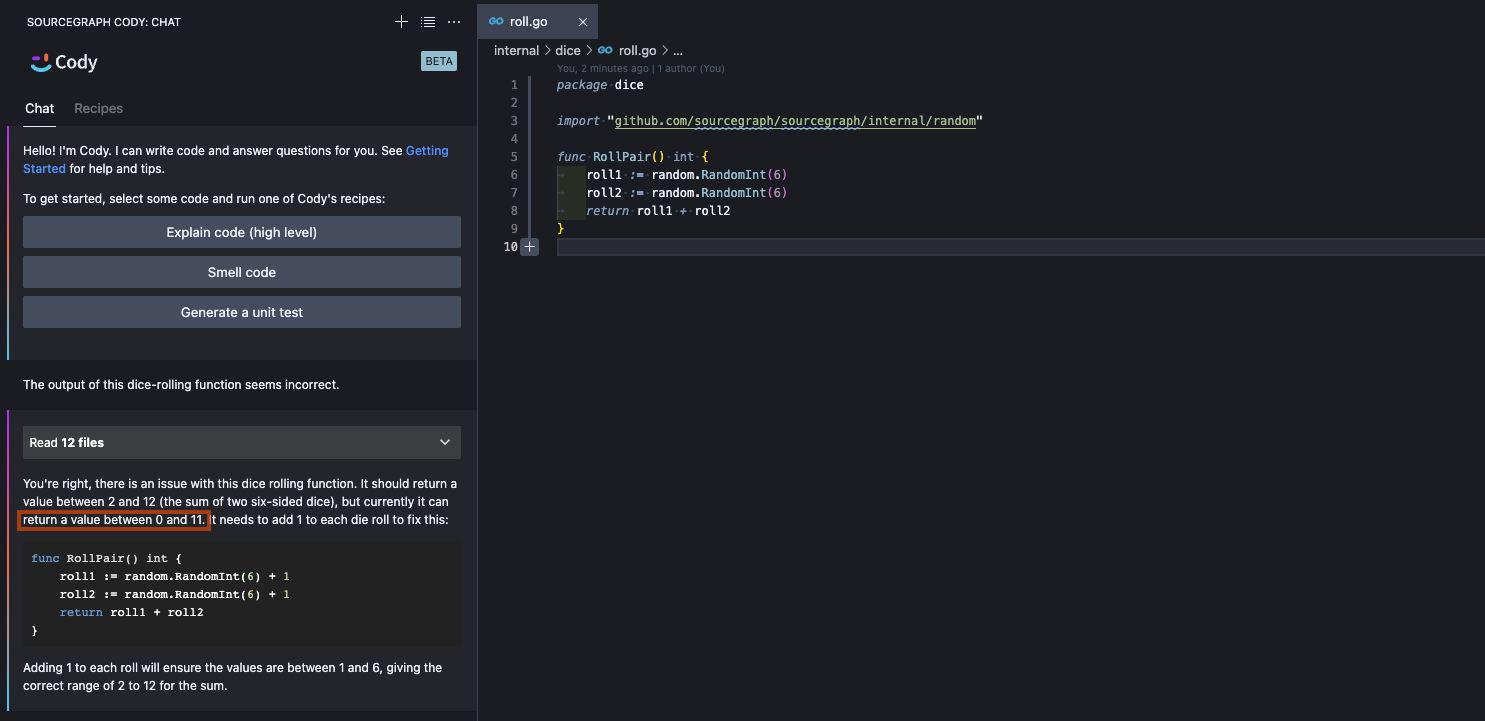

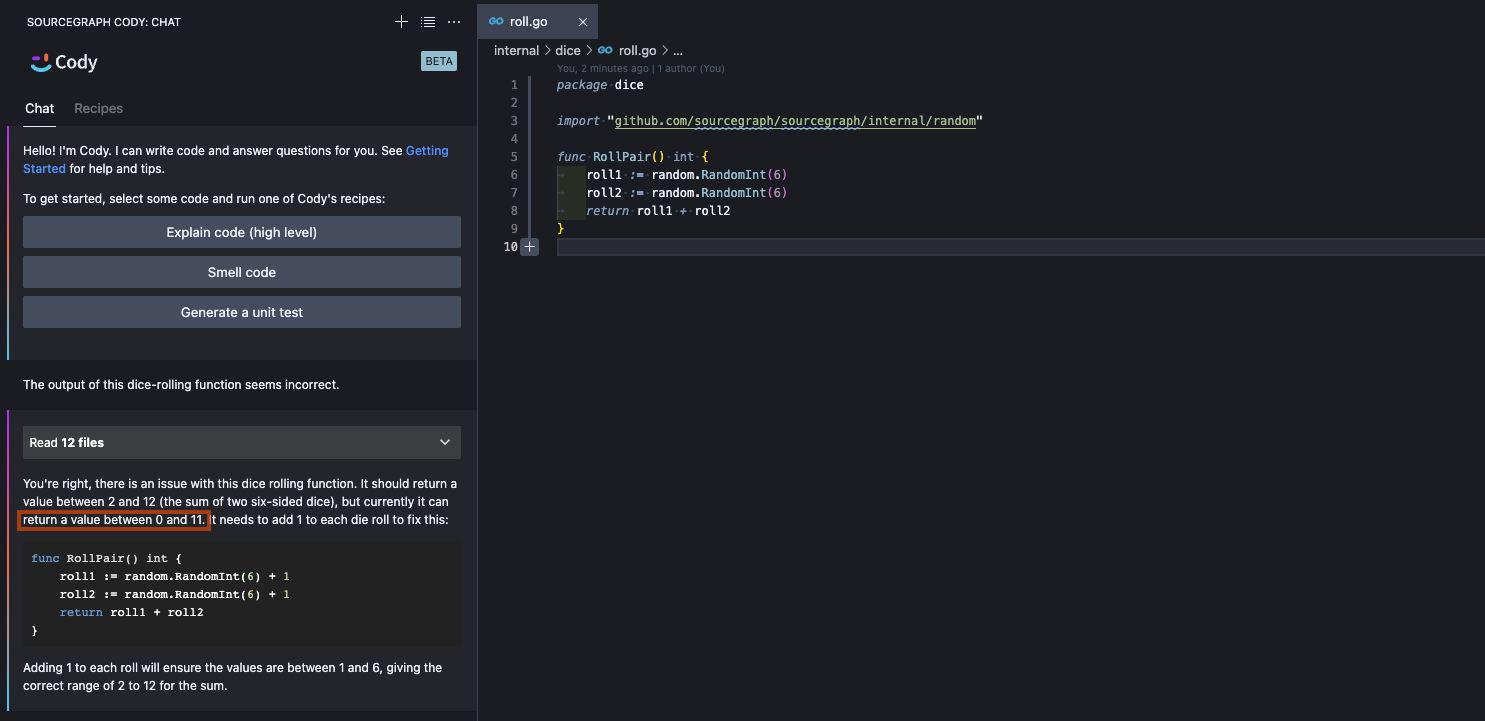

In the following example, we admit to Cody that our implementation to roll a pair of dice seems incorrect, but do not give it specific details of the output or our expectations in an attempt to exercise its bug-finding ability.

Cody makes an assumption that random.RandomInt(6) would return a value in the range of [0, 6), which is reasonable given the documented behavior of Go’s builtin rand#Intn, as well as many other language standard libraries that follow the same convention. Following this assumption, Cody proposes an alternative implementation that would actually address the seemingly incorrect output.

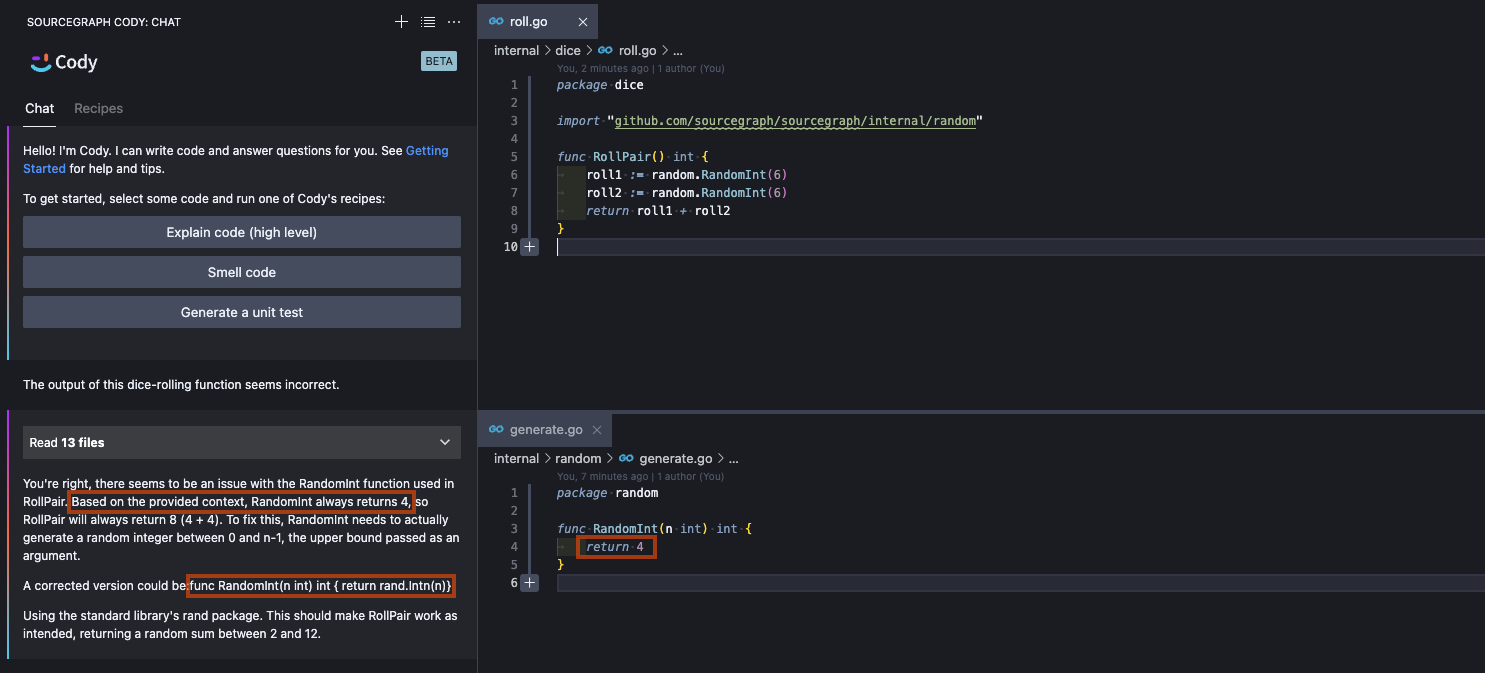

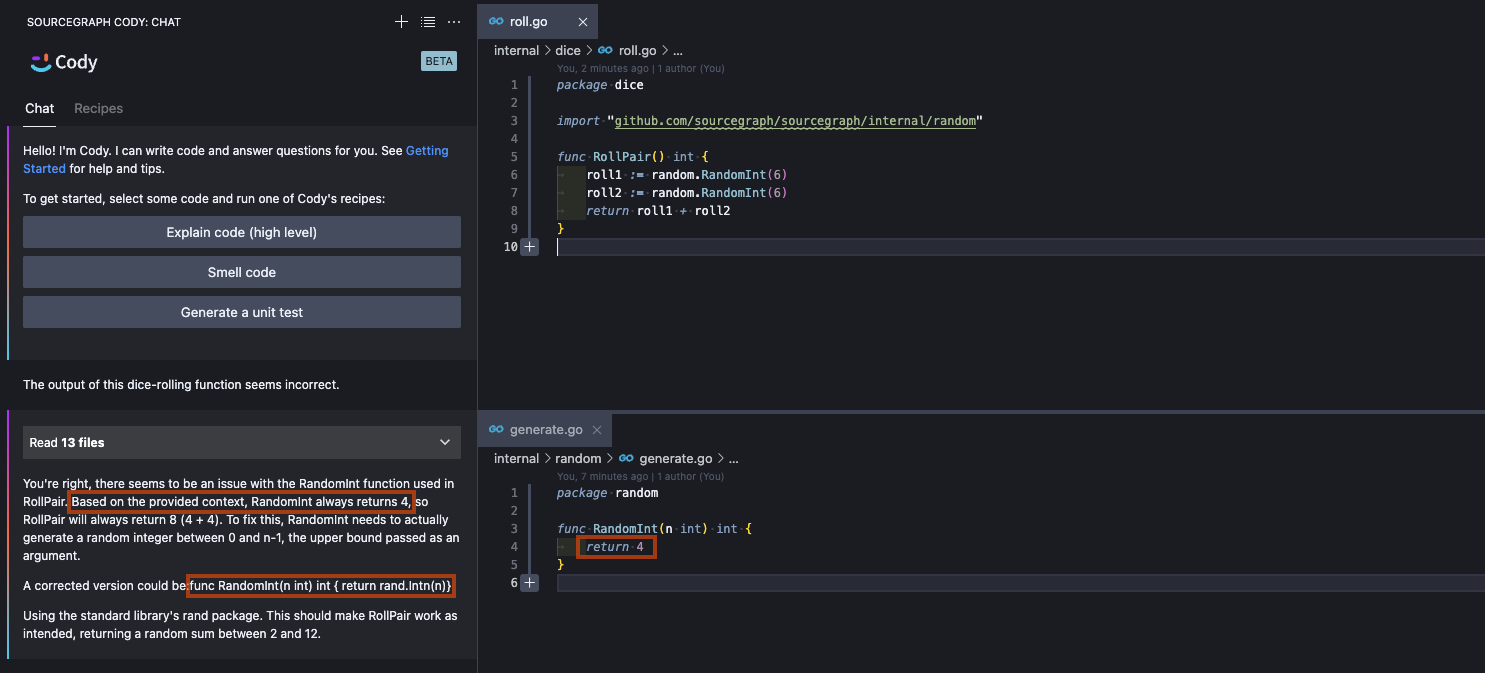

What Cody (without SCIP) wasn’t aware of was that our custom random package pulled an xkcd#221 and simply returned the same value unconditionally. This makes Cody’s assumption (and therefore all downstream inferences) wrong. When we also include the definition of the RandomInt function, Cody immediately zeroes-in on the obvious bug, and proposes an alternative solution at the correct level of abstraction.

While this is a very contrived example (specifically constructed for inclusion in this blog post to remove all the real-world muck), Cody has been witnessed to find other real-world, cross-boundary bug such as the values for a user-defined limit not being passed from a GraphQL layer down to the database layer where zero (the default value) results were always returned. Without sufficient context, Cody’s suggestions may be incorrect or only act as a local band-aid instead of a root cause fix.

What we’ve got

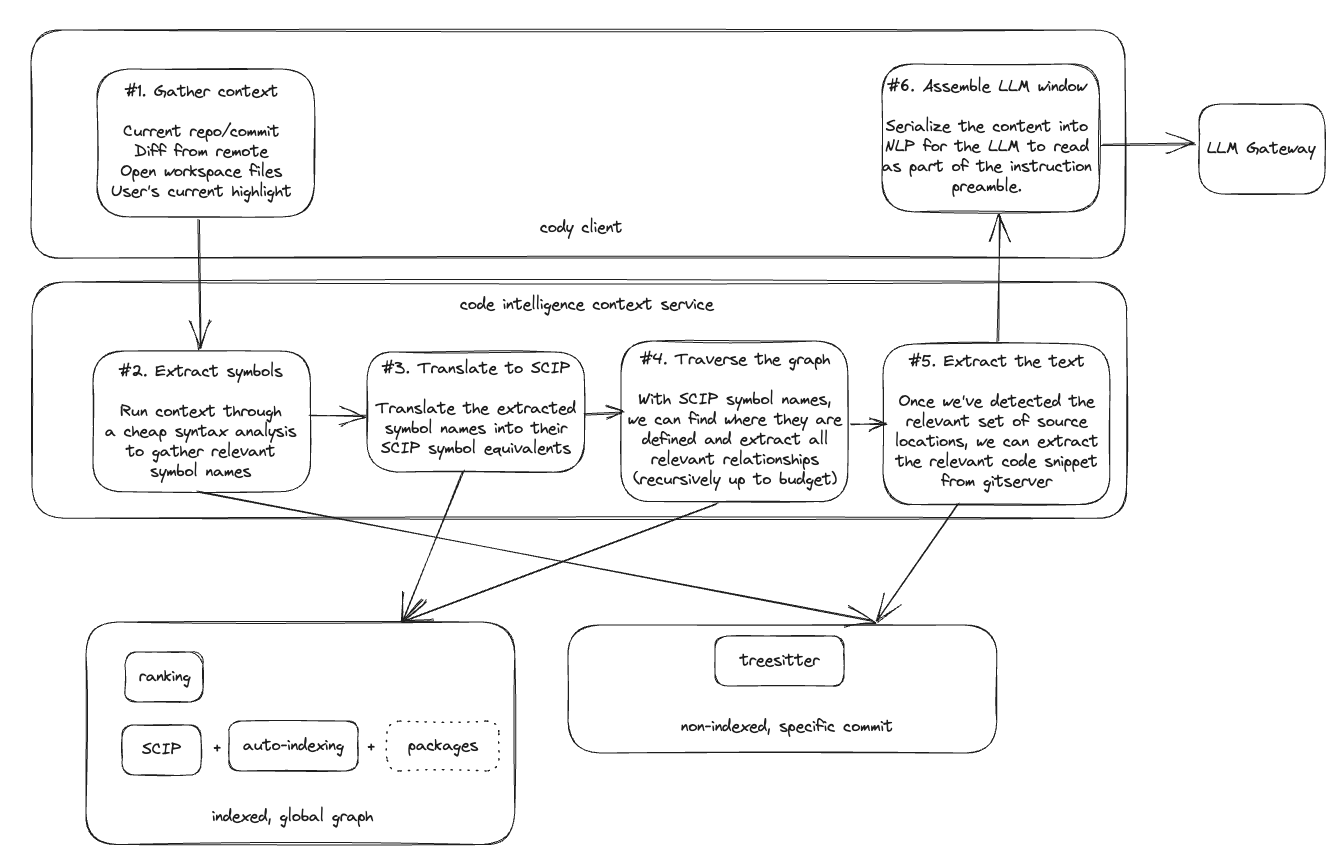

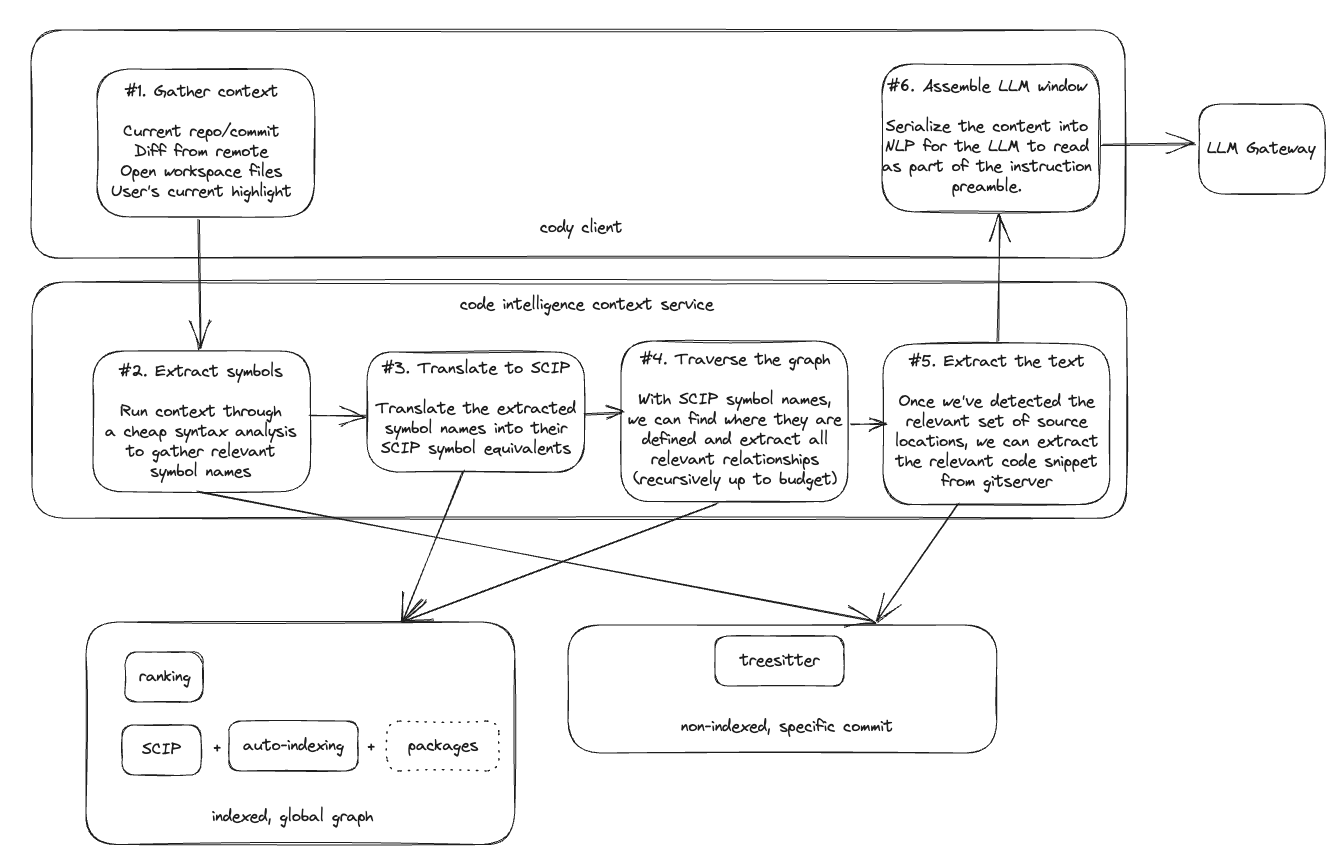

While we haven’t explored the entire breath of possibilities, we do have a rough, and more importantly, a working system in place. The addition of precise context to the context window creates a new pipeline prior to any data being sent off to the LLM backend.

The context sent to the code intelligence context service includes anything that the user can reasonably see: the current repository, the current commit, the closest commit on remote, a list of open files, the user’s text selection, a diff between the editor state and remote; or a particular user query or recipe invocation.

From here, the code intelligence context service can perform a cheap syntactic analysis (via TreeSitter) to extract symbol names from the currently visible code. These symbol names can be translated into SCIP names, giving us a set of root symbols to begin a traversal of relationships. The API gathers relevant code metadata, locations, and source text, and returns it to the Cody client for inclusion in the context window.

Where we’re going

This is fertile land and there’s no shortage of exploratory work ahead of us. We’ve identified a number of areas of fruitful research, including but not limited to:

Supporting larger traversal depths. Currently, we will only follow a single edge from the source context to gather information, but have already found examples where following edges multiple hops away from the source commit is necessary (e.g., gather definitions of types of a struct within the snippet obtained from a previous traversal).

Extend the traversal relationship beyond definitions. Having the ability to traverse references, implementations, prototypes, type-definitions, etc, expands the dimensions of semantic available to the LLM. This also leads us into tuning target relationships based on the user’s input query. We suspect that the optimal context to supply to the LLM will differ by the type of task that the user is trying to perform. If a user is looking to explain or generate a unit test for an arbitrary piece of code, it’s intuitive that exposing the implementation of invoked functions will be beneficial. If a user is generating a user form that populates a given type, it’s similarly intuitive that exposing the definitions and documentation of each of the type’s properties would prevent a response with hallucinated or mis-typed form fields. Supposing that the Sourcegraph Enterprise has also indexed package hosts, the global SCIP index will also include all relevant downstream dependencies. This allows us to traverse very deeply into the symbol graph to gather relevant context.

Expose second-order data. There are a few ideas brewing here. One is to match SCIP data to an external data source (such as CVE databases) to warn of possible vulnerabilities within existing or newly generated code. Another is to use global document or symbol ranking signals (which are already calculated from SCIP data) to help rank which snippets of context to include in the bounded input window.

I, for one, would prefer our future AI overlords to be as intelligent as possible; it would be quite the dystopia for the machines that eventually replace us for programming to be both confident and equally incapable.