We have recently identified the root cause of a frequent, insidious pain point related to database migrations during Sourcegraph version upgrades. Many users handling the installation and upgrade of their Sourcegraph instance can likely attest to seeing an error similar to the following midway through an upgrade from one minor release to the next.

ERROR: Failed to migrate the DB. Please contact support@sourcegraph.com for further assistance: Dirty database version 1528395797. Fix and force version.

This error message is the bane of a growing number of site administrators as well as any engineer in our customer support org or any engineer in our #opsgenie Slack channel.

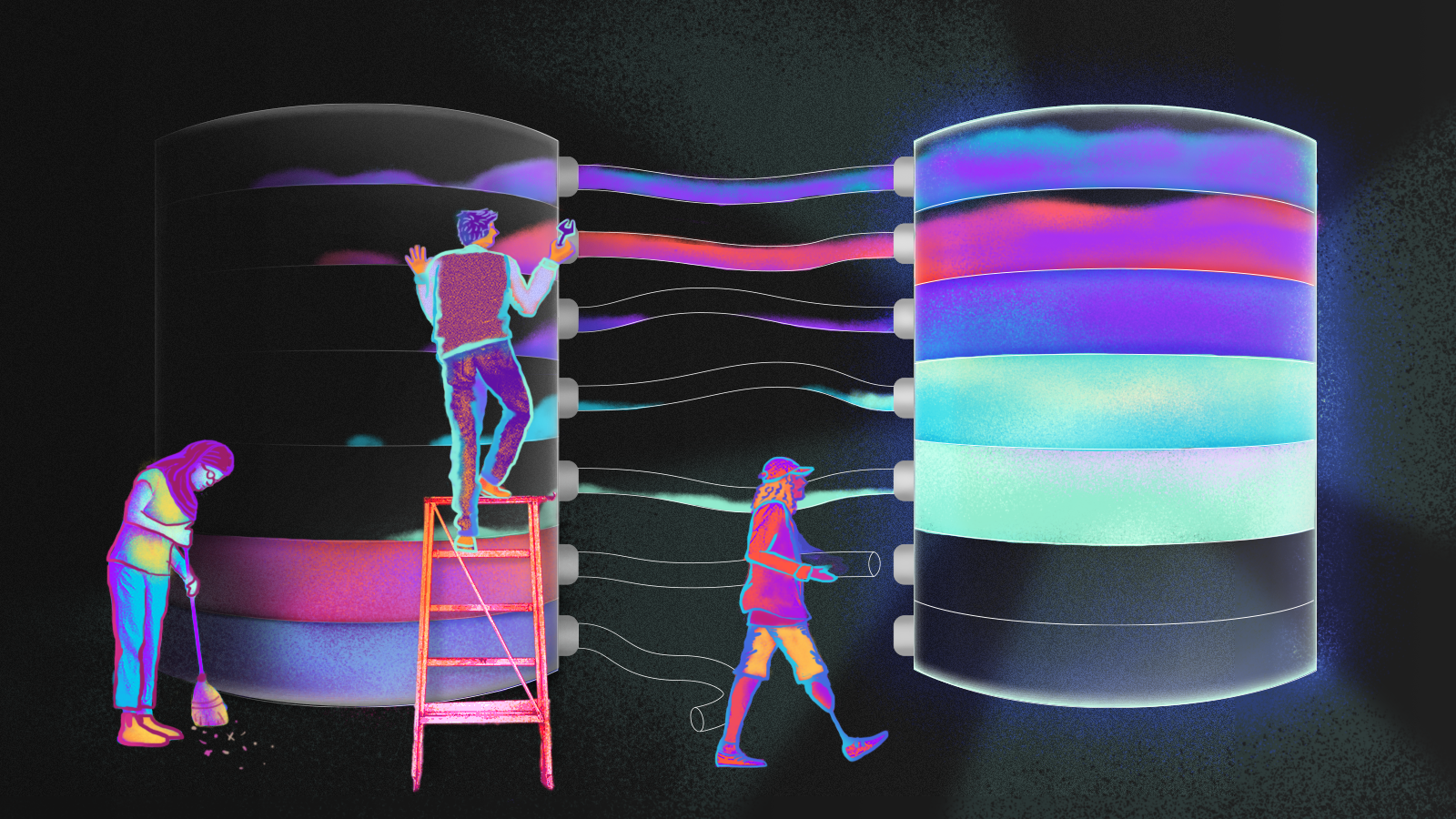

As of Sourcegraph 3.37, we no longer spuriously mark the database as dirty during common upgrade scenarios. We have decoupled database migrations from the application start up sequence to better control database schema upgrade conditions.

This release adds:

- New tools that allow site administrators to run database migrations independently from an upgrade. Large database instances can be upgraded ahead of time of a general application upgrade to reduce the possibility of downtime due to migrations taking longer than the health check timeout.

- Better error messages and a better recovery process in the (now rare) case of a real database migration failure.

- A general pruning of now-irrelevant troubleshooting documentation.

We’ve tried to make this transition as seamless as possible, and there should be no manual steps required to proceed to Sourcegraph 3.37.0 and beyond. If we’ve done everything right, you’ll notice no differences.

But, if you’d like to see how the sausage is debugged, read on.

The issue

Upgrades of Sourcegraph instances, including on-premise deployments and our Cloud environment, would often fail with a dreaded “dirty database” error. This class of error left the Sourcegraph instance in a broken state that required manual intervention to resolve.

On the customer side, the resolution was inelegant. A new container would come online and attempt to migrate the database. When this attempt failed, the database was marked as dirty and the container would restart. New instances would see the dirty flag set and also restart. Site administrators would notice rapidly restarting containers (that, or a wonky Sourcegraph experience) and would sometimes find a log message asking them to contact support for assistance.

In our Cloud environment, Sourcegraph engineers endured the same manual process.

Requiring site administrators to directly modify database contents is not a distribution practice we should encourage. The frequency of these errors and the rising burden put on users and application/product engineers made this a pressing issue to resolve.

Identifying (a) contributing factor

In our original effort to eradicate this class of error, we incorrectly attributed the Docker container health check period as the primary cause. Our intuition was built from two observations:

- We never saw this issue in local development, which usually operates over relatively small sets of data.

- We saw this issue frequently in our Cloud environment, but exclusively on objects over a particular (but undetermined) size, such as our repository or code intelligence data tables.

We believed that the issue occurred if and only if the set of migrations running on application startup could not finish within the parent container’s health check timeout. If the migration took longer to perform than the configured timeout, Kubernetes would declare the pod dead and restart it. Killing a pod during an active migration marks the database as dirty until the site administrator manually resolves the issue.

And this is exactly the behavior we see.

Our original solution, simply “decoupling” the database from application upgrades, targeted the Kubernetes health check as the primary problem. By performing the migrations separately from the application deployment, the migration process no longer has to complete within a configured health check timeout of a downstream application. By having a separate component perform the migrations, and by moving away from our dependency on a third-party migration library, we can better inspect the health of the migrator and the progress of its migration attempts.

The first draft of the migrator service kept all other behavior the same. We explicitly kept the new migration behavior as close to the previous migration behavior as possible–just running in a different container–to avoid turning too many knobs at once. Part of the behavior we explicitly did not change was how we handle concurrent migration attempts.

Each migrator attempts to take an advisory lock over a shared key representing the target schema. If the lock is acquired, the current database schema version is read. If the database is marked as dirty, the migrator panics. If the database is up to date, the migrator can exit. Otherwise, all unapplied migration files are applied and the lock is released.

After some initial testing, we discovered that the frequency of “dirty database” behaviors did not actually decrease. The solution did not address the symptoms, and we needed to do more.

A deeper contributing factor

Over time, our engineering organization formed some tribal knowledge regarding ways to avoid “taking down production” with poorly defined migrations. Creating indexes on tables that can have a large number of rows caused many to hesitate. Normal index creation operations take an exclusive write lock on the table, creating the new index from the existing table data synchronously. During this time no inserts, updates, or deletes can be made to the table. You basically incur write downtime (along with a blip of failed requests in your metrics dashboards and alerting systems, and a slice of failed jobs that failed in the background) for the table, which can take tens of minutes for large tables.

For our use case, CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY was received as a hero.

Using concurrent index creation reduced downtime incidents in our Cloud environment related to heavy database contention triggered by continuous deployment.

Using concurrent index creation also introduced a footgun and plenty of friendly fire that we didn’t recognize until recently. Concurrent index creation is performed in three distinct phases to ensure that a full table lock is never required. That way, neither readers nor writers are not blocked for long stretches of time.

- Phase 1: Create new catalog structures for the index, but do not begin to populate them yet. Transactions that started before the completion of this phase will only see (and therefore only write to) the old catalog structures.

- Phase 2: Wait for all transactions starting before the end of Phase 1 to finish. Then, perform a full-table scan and write the content of each row to the new index structure. Open the new index structure up to writes.

- Phase 3: Wait for all transactions starting before the end of Phase 2 to finish. Then, perform another full-table scan and write the content of each row inserted during Phase 2 to the new index structure. The old index structure can now be closed to writes.

There’s a particular detail here that deserves special attention in hindsight: concurrent index creation operations block until all transactions started before them have either committed or rolled back. Mixed with long-held advisory locks, we encounter the rather nasty situation below.

Observe! In psql Process A, we acquire an advisory lock:

| |

In psql Process B, we attempt to acquire an advisory lock:

| |

Because this lock is already held by another process, this command blocks indefinitely–or until the user gets bored and aborts their session.

Back in psql Process A, we attempt to create an index concurrently on literally any table:

| |

After a second or so, the PostgreSQL deadlock detector kicks in, notices two processes vying for each other’s locks, and cancels the deadlocked index creation operation. This error is a bit dense, but states that the index creation operation is waiting for Process B’s attempt to acquire the advisory lock to finish, but the advisory lock acquisition is blocked on Process A’s ownership of that lock.

Concurrent index creation failures are also a particularly nasty failure mode, because they leave the database with a partially created index that exists in the system catalog but is accessible to reads or writes. To resolve this database state, the invalid index has to be dropped and re-created. This is an easy step to forget because you need to do it manually, and forgetting the step can have severe performance penalties if you don’t detect it.

Let’s make a few more observations:

- We have increasingly relied on concurrent index creation to ensure that we don’t reduce write throughput during continuous deploys.

- We respond to a reduction of pods due to a dirty database, but do not pay particular attention to the original error condition. In fact, any original error (SQL, network, timeout, or deadlock) may have often been obscured by a unrelated bug that occurs when two error libraries we use interact in a certain way: cockroachdb/errors and hashicorp/go-multierror. (We’re currently investigating this issue as well, so stay tuned for another blog post!)

- We deploy to Cloud by starting new services that immediately attempt to run migrations.

The first observation serves as loose evidence of a correlation between concurrent index creation and dirty database issues. This correlation does, albeit unscientifically, match reality.

The second observation implies that we never actually check the error message that occurs when the database was first marked as dirty. Looking back, a number of downtime incidents we originally attributed to migrations not completing within our Kubernetes health check timeout are also explainable by this deadlock condition. We’ve been increasingly relying on concurrent index creation, and any contention of a migration advisory lock will cause the deadlock to occur. And, by the third observation, we have plenty of lock contention when multiple pods start up at the same time looking to update the database.

With a new theory in hand, we can finally attack the problem in a focused manner.

We changed the migration process to gracefully deal with concurrent index creation by dropping the advisory lock and instead coordinating with concurrent migration attempts within the PostgreSQL catalog itself. Of particular interest is the pg_stat_progress_create_index system view, which reports index creation progress. The migrator is also intelligent enough to detect invalid indexes and repair them rather than flagging a human to hold its hand.

After another round of testing, migrations finally behave according to intuition.

Conclusion

We’ve long since outgrown the way in which we run database migrations. We’ve known for a while that there was a problem, and felt the pain along with our users for an embarrassingly long time. After digging a bit deeper, better understanding the problem space, and breaking a bit of our ossified code and deployment process along the way, we can now deliver a significant quality of life improvement to our users and Sourcegraphers alike.

If your next upgrade does not crash, please tweet me at @ericfritz.

Related resources

We’ve updated several documentation pages which are worth a look for existing site administrators:

- How to run

migratoroperations - How to troubleshoot a dirty database

- Rolling back a PostgresSQL database

Check out some of the higher-scope code changes that made this change possible: